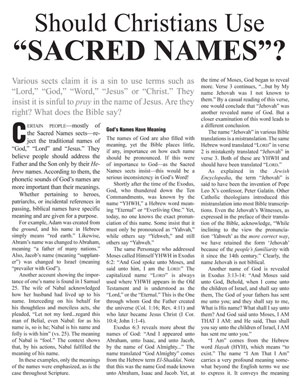

Certain people—mostly of the Sacred Names sects—reject the traditional names of “God,” “Lord” and “Jesus.” They believe people should address the Father and the Son only by their Hebrew names. According to them, the phonetic sounds of God’s names are more important than their meanings.

Whether pertaining to heroes, patriarchs, or incidental references in passing, biblical names have specific meaning and are given for a purpose.

For example, Adam was created from the ground, and his name in Hebrew simply means “red earth.” Likewise, Abram’s name was changed to Abraham, meaning “a father of many nations.” Also, Jacob’s name (meaning “supplanter”) was changed to Israel (meaning “prevailer with God”).

Another account showing the importance of one’s name is found in I Samuel 25. The wife of Nabal acknowledged how her husband had lived up to his name. Interceding on his behalf for his thoughtless and merciless acts, she pleaded, “Let not my lord...regard this man of Belial, even Nabal: for as his name is, so is he; Nabal is his name and folly is with him” (vs. 25). The meaning of Nabal is “fool.” The context shows that, by his actions, Nabal fulfilled the meaning of his name.

In these examples, only the meanings of the names were emphasized, as is the case throughout Scripture.

God’s Names Have Meaning

The names of God are also filled with meaning, yet the Bible places little, if any, importance on how each name should be pronounced. If this were of importance to God—as the Sacred Names sects insist—this would be a serious inconsistency in God’s Word!

Shortly after the time of the Exodus, God, who thundered down the Ten Commandments, was known by the name “YHWH,” a Hebrew word meaning “Eternal” or “Everliving One.” Yet, today, no one knows the exact pronunciation of this name. Some insist that it must only be pronounced as “Yahvah,” while others say “Yehweh,” and still others say “Yahweh.”

The same Personage who addressed Moses called Himself YHWH in Exodus 6:2: “And God spoke unto Moses, and said unto him, I am the Lord:” The capitalized name “Lord” is always used where YHWH appears in the Old Testament and is understood as the “Lord,” or the “Eternal.” This is the One through whom God the Father created the universe (Col. 1:16; Rev. 4:11) and who later became Jesus Christ (I Cor. 10:4; John 1:1-4).

Exodus 6:3 reveals more about the names of God: “And I appeared unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, by the name of God Almighty...” The name translated “God Almighty” comes from the Hebrew term El-Shaddai. Note that this was the name God made known unto Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Yet, at the time of Moses, God began to reveal more. Verse 3 continues, “...but by My name Jehovah was I not known to them.” By a casual reading of this verse, one would conclude that “Jehovah” was another revealed name of God. But a closer examination of this word leads to a different conclusion.

The name “Jehovah” in various Bible translations is a mistranslation. The same Hebrew word translated “Lord” in verse 2 is mistakenly translated “Jehovah” in verse 3. Both of these are YHWH and should have been translated “Lord.”

As explained in the Jewish Encyclopedia, the term “Jehovah” is said to have been the invention of Pope Leo X’s confessor, Peter Galatin. Other Catholic theologians introduced this mistranslation into most Bible transcriptions. Even the Jehovah’s Witnesses, as expressed in the preface of their translation of the Bible, acknowledge, “While inclining to the view the pronunciation ‘Yahweh’ as the more correct way, we have retained the form ‘Jehovah’ because of the people’s familiarity with it since the 14th century.” Clearly, the name Jehovah is not biblical.

Another name of God is revealed in Exodus 3:13-14: “And Moses said unto God, Behold, when I come unto the children of Israel, and shall say unto them, The God of your fathers has sent me unto you; and they shall say to me, What is His name? What shall I say unto them? And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM: and He said, Thus shall you say unto the children of Israel, I AM has sent me unto you.”

“I Am” comes from the Hebrew word Hayah (HYH), which means “to exist.” The name “I Am That I Am” carries a very profound meaning somewhat beyond the English terms we use to express it. It conveys the meaning of the “Self-Existent One” or the “One Who Is.”

The name I AM THAT I AM only has meaning in the language one is using—understanding. The true God appeared to Moses and instructed him that He was, in effect, “the God who is,” as opposed to “the many gods who are not.” The true God defines Himself as the God who exists, when others do not.

A New Testament example of “I AM” is found in John 8:58: “Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I AM.” Here, the term “I AM” means the very same thing as the term used in Exodus 3:14. Both mean “to exist” and refer to the Self-Existent One—who became Christ. Certainly, Christ existed before Abraham, because He was the One who created all things (Eph. 3:9).

What meaning does any of this have to an Englishman if he must only say it in Hebrew?

If our salvation rested upon how we pronounce the name YHVH, then God would have made this crystal clear in His Word. Those who make the detailed pronunciation of God’s names a primary issue for salvation have the wrong priorities. Indeed, we are to reverence and fear God the Father and Jesus Christ His Son. Nowhere does the Bible require God’s people to accurately pronounce His Hebrew names in order to achieve salvation.

Thirty-one times in the first chapter of Genesis, the word “God” comes from the Hebrew word Elohim, a uniplural word indicating more than one Being in the God Family. It means “mighty ones.” The singular term for Elohim is El, which means “a mighty one,” and is also translated “God.” When used with certain other Hebrew words, the term El prefixes a variety of names for God, each emphasizing different attributes of His nature and character.

Sacred Names advocates claim that they elevate God’s names by expressing them exclusively in Hebrew. Actually, just the opposite occurs. This practice diminishes them—and the meaning they are intended to convey—by substituting an ancient language that hides the real meaning behind a foreign-sounding utterance.

In the English language, the term “Eternal” means “without beginning or end, perpetual, and lasting throughout eternity.” Suppose this English term is substituted where someone is describing a concept in the Chinese language or perhaps in Sanskrit. Substituting the English term for “Eternal,” instead of the translated equivalent term in their spoken language, would create a void in the intended thought. Likewise, the substituting of the names of God in Hebrew serves to hide the meaning behind them. Since the names attributed to God are not without meaning, the act of masking them in an ancient language serves to cloud or hide the honor intended to be conveyed by those names.

How Pronunciation Became Lost

The Hebrew language does not use vowels—only consonants and semi-consonants. The pronunciation of “YHWH” was once well understood among the Hebrews. (It is interesting that YHWH comes from the root word in Hebrew HYH—an old form of the root HWH, meaning be.”)

Israel and Judah had come to forget God’s name. They actually came to superstitiously fear His name, choosing never to pronounce it. This was partly because they made an idol out of His name and partly because of their resentment against Him for punishing them. Out of superstitious reverence and fear, they refrained from repeating the name YHWH, though they knew how to pronounce it. Instead, they chose to use, and say aloud, the word Adonai, meaning “Lord” or “Master,” wherever YHWH appeared in the text.

Thus, the correct pronunciation of YHWH was forgotten. Notice: “I have heard what the prophets said, that prophesy lies in my name, saying, I have dreamed, I have dreamed. How long shall this be in the heart of the prophets that prophesy lies? Yes, they are prophets of the deceit of their own heart; Which think to cause My people to forget My name by their dreams which they tell every man to his neighbor, as their fathers have forgotten My name for Baal” (Jer. 23:25-27).

Because of the false belief that the name YHWH was too holy to be uttered, its pronunciation became forgotten. And without knowing the vowels, one cannot possibly know how to correctly pronounce God’s name. The precise way of pronouncing YHWH is not known today, but its meaning is preserved in Scripture.

Hebrew will not be the language in the soon-coming kingdom of God. God will reverse the dividing of languages that He caused at the tower of Babel and initiate a universal language: “For then will I turn to the people a pure language, that they may all call upon the name of the Lord, to serve Him with one consent” (Zeph. 3:9).

If this coming pure language were to be Hebrew, this verse would have said so. Indications are that it will be a new language—having simplicity and clarity, free from dubious misunderstandings due to confusion over pronunciation of terms. This eliminates Hebrew, which, with its absence of vowels, causes endless disputes—even among the Sacred Names groups, who can never agree which pronunciation is the most correct or acceptable.

However, suppose one became convinced by the Sacred Names arguments and decided to join their movement. Would this decision settle the matter in his mind? Not at all!

The many Sacred Names groups are hopelessly divided as to how the Hebrew names of God should be pronounced. And, since nothing equivalent to vowels exists in written Hebrew (oral Hebrew generally uses them), further division among these groups will continue.

Again, some groups use Yahveh, others Yahweh, others Yehweh, still others Yahvah or Jehovah, and still others Joshua or Yeshua or Joheshua—and many, many more!

It is difficult to imagine that God would decree that His names could only be pronounced in a particular language, but leave His would-be worshipers in utter confusion as to the right way to pronounce them. While this entire matter is marked by confusion, God could not be its author (I Cor. 14:33)!

God’s Names Translated in Scripture

As previously stated, all Sacred Names sects insist that only the Hebrew names of God, properly pronounced in Hebrew, are acceptable to Him. However, when we find God’s names translated into different languages, their claims lose even more credibility.

After the Babylonian captivity, Hebrew ceased to be the common language among the Jews and was replaced with Aramaic. Five chapters of Daniel were written in Aramaic, with the rest in Hebrew. Four chapters of Ezra were also written in Aramaic, with the rest in Hebrew. In these chapters, we find God’s name—Elah—written in Aramaic, not Hebrew. Daniel and Ezra were God’s dedicated servants, and they were not bound to only write (or speak) the names of God exclusively in the Hebrew language. Clearly, Daniel and Ezra, inspired by God, properly translated His name into Aramaic. Therefore, the Hebrew names for God can be translated into other languages, as well.

While the true names of God were often interchanged with the names of pagan gods and idols, such acts by misguided human beings does not taint His names. Romans 1:21-23, 28 records that the ancients’ refusal to honor God returned upon their own heads—yet God’s honor was not diminished. Some Sacred Names sects actually use this weak argument to completely prohibit the speaking of God’s names. They do this to justify their “preservation” of hidden Hebrew terms for God in order to maintain “purity” of His name.

God’s Names in the New Testament

When the apostles wrote the letters that became Scripture, Greek was the universal language in the Roman Empire. The Jewish historian Josephus confirms that Greek was predominant throughout the Roman Empire and that it was second only to Aramaic among the Jews in Judea (Antiquities of the Jews, bk. XX, ch. XI, sec. 2).

Much of the New Testament consists of letters from the apostle Paul, addressing primarily Greek-speaking Gentiles. Paul’s many references to the Father and Christ were not confined to the Hebrew language. He spoke to the New Testament Church in Greek.

God inspired Paul to express the Hebrew word El as the Greek word Theos—both terms mean “God.” Likewise, he was inspired to express the Hebrew word, YHWH, into the Greek word Kyrios—translated “Lord.” In fact, both Greek words can mean either “Lord” or “God.”

Christ inspired the writers of both the Old and New Testaments. He inspired Paul and other apostles to write the names of God directly into the Greek. Nowhere in the New Testament do we find that the apostles exclusively used the Hebrew names for God.

Even when Paul wrote the book of Hebrews in the Hebrew language, it was translated by Luke shortly thereafter into Greek. This translation served to help not only the Gentile brethren, but also most of the Jews. Hebrew was rarely spoken during this time, even among the Jews. Paul’s letter to the Hebrews was written in Hebrew in order to gain the attention of the inner circle of religious Jews. This letter was translated, and also exclusively preserved, in Greek. This was also the case for the gospel of Matthew.

Sacred Names sects claim that the bulk of the New Testament was originally written in Aramaic. They strive to downplay the preponderance of Greek during the apostolic era. Since their goal is to promote only God’s Hebrew names, they would support Aramaic because it is a step closer to Hebrew. But it is nonetheless a separate and distinct language!

Acknowledging that Luke was written in Greek, the Sacred Names proponents contend that the gospels of Mark and John were written in Aramaic. We can prove that this is not true by carefully examining Mark 15:34: “And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? Which is, being interpreted, My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”

This matter is self-explanatory. Mark records the Aramaic quote verbatim, followed by the interpretation in Greek. If Aramaic were the original language of the book of Mark, there would be no reason to “interpret” the Aramaic quote. Everyone who spoke Aramaic would have automatically known what was said. This proves that Aramaic was not the original language of the book of Mark.

There are a number of other instances in the New Testament in which Aramaic phrases are interpreted into Greek in a similar manner. Yet, the Greek is always translated word-for-word, without ever being interpreted. An interesting clarification is found in John 1:41: “He [Andrew] first found his own brother Simon, and said unto him, We have found the Messiah, which is, being interpreted, the Christ.” The word “Messias” is the Greek spelling for the Hebrew word “Messiah.” Messiah means “the Anointed.” Since the Greek-speaking people were not familiar with Messias, John translated the word into Christos, meaning “the Anointed One.” Hence, John translated one Greek word borrowed from the Hebrew into another Greek word more familiar to those of the Greek language—the universal language of that day.

Sacred Names sects all favor the word Messiah over Christos. But clearly, John translated Messiah as “Christ,” indicating approval and traditional use of that term.

The Sacred Names sects also reject the name “Jesus.” Admittedly, this name is greatly overused by many modern evangelicals. But, we should not allow this—what amounts to their vain repetition—to diminish our appreciation of Christ’s name.

The English word “Jesus” derives from the Greek word “Iesous,” which means “the Eternal is the Savior.” This name is equivalent to the Hebrew name Joshua. In Hebrews 4:8, the translators left the term in the Greek, instead of properly translating it back to Joshua. Iesous became the personal name of Christ and was used over 910 places in the New Testament. “Jesus” is ultimately derived from YHWH.

Consider this. We also find “Word” as one of Christ’s names: “And He [the Lamb—Jesus Christ] was clothed with a vesture dipped in blood: and His name is called The Word of God” (Rev. 19:13).

At the beginning of his gospel account, John also referred to Christ in this way: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

God’s Church Carries His Name

If God’s name were only allowed to be spoken as some unknown Hebrew word, then this same mysterious name would be attached to His Church. Christ stated, “And now I am no more in the world, but these are in the world, and I come to You. Holy Father, keep through Your own name those whom You have given Me, that they may be one, as We are” (John 17:11).

In twelve different New Testament passages, the Church is referred to as the Church of God—kept through the Father’s name. That Church is not known as the Church of El-Shaddai or the Church of YHWH, but simply the Church of God!

One of the collective terms used for the Church is found in I Thessalonians 2:14: “For you, brethren, became followers of the Churches of God which in Judea are in Christ Jesus: for you also have suffered like things of your own countrymen, even as they have of the Jews.” Acts 20:28 is an admonition for the elders to feed the “Churches of God.”

The terms “Churches of God” and “Church of God” were used by the very apostles appointed by Christ. If these were improper names for the Church, then this would not be the case. Anyone who denies the use of the word “God” in association with His Church is missing the point of Scripture.

Consider: The Church of God was led for 52 years in the twentieth century by Herbert W. Armstrong, who also held the office of apostle. God’s blessings were very evident during that phase of His Work, and Mr. Armstrong was used by God to restore a vast array of true doctrines to His Church. Could the same God who led Mr. Armstrong in this way not also lead him to understand His own name?

Sacred Name Groups in Disarray

As alluded to earlier, advocates of sacred name usage are hopelessly divided. They are unable to agree upon detailed pronunciations of sacred names that are the centerpiece of their movement. Therefore, the few groups that constitute their ranks will continue to exist independently.

Matters of truth and doctrinal purity are given less emphasis in these groups than the correct pronunciation of these names. This leads to another dominant characteristic of that movement—extensive doctrinal error. Such a condition is inevitable, because such error always begets more of the same (Gal. 5:9).

Another noticeable trait of those in the sacred names movement is an accusative spirit toward others outside their domain. Since they consider the precise usage of a phonetic sound as most pleasing to God, they therefore view themselves as having “special knowledge” that places them above those in other groups.

Glorify God’s Name

Matthew 10:33 shows the importance of not denying the name of Jesus Christ in word or action: “But whosoever shall deny Me before men, him will I also deny before My Father which is in heaven.”

We have seen that the names of the Father and the Son are not to be spoken exclusively with an unknown Hebrew pronunciation. Rather, we find them freely translated into other languages—disproving the claim that only the Hebrew names of God should ever be used. The Word of God is a living Book, to be read and understood in living languages!

Those whom God calls must worship Him in spirit and in truth (John 4:23), and must not be at a loss to call upon His name: “Give unto the Lord the glory due unto His name; worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness” (Psa. 29:2). God is presently known only by those He has called out of this world.

In the world to come, God’s name will be called upon by all humanity: “All nations whom You have made shall come and worship before You, O Lord; and shall glorify Your name” (Psa. 86:9)!