Reuters/Andrew Kelly

Reuters/Andrew Kelly

World News Desk

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowReuters – More than a year and a half after the COVID-19 pandemic ruptured the U.S. job market in historic fashion, huge gaps in employment and the labor force remain despite unprecedented demand for workers and a record number of vacant jobs.

Policymakers are struggling to understand just what is keeping so many people from returning to work—or even looking for a job. Friday’s monthly payrolls report showed strong hiring in October but the labor force participation rate tracking the share of people either working or searching for jobs did not budge.

“There’s room for a whole lot of humility here as we try to think about what maximum employment would be,” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said last week after the central bank’s latest policy meeting.

Moments that were expected to mark turning points in the labor market recovery, such as the start of the school year or the expiration of enhanced unemployment benefits, did not lead to a massive return to the workplace.

Instead, economists are learning, workers may be stepping back because of family responsibilities, concerns about the virus or the desire to do something new.

Here is a look at the questions experts say could help determine what the labor market could look like as the pandemic fades.

• How many people are not working because of the virus?

That remains hard to pin down, but Friday’s data did signal some improvement. About 3.8 million people were unable to work or reported reduced hours due to their business closing or reducing operations, down from roughly 5 million in September, resuming a downward trend that was interrupted by a rise in August.

Those saying they did not look for work because of the pandemic declined to 1.3 million last month from 1.6 million in September, the first notable drop since June.

• Will retirees come back to the labor force?

Retiree ranks increased by 3.6 million from February 2020 to June 2021, greater than the 1.5 million retirements that would have been expected under the pre-pandemic trend for retirements, according to the Kansas City Fed. That was driven by a big drop in those moving from retirement back to work, likely because of health concerns. More baby boomers also left the labor market.

Fed Board Governor Michelle Bowman said last month surging retirements “may make it harder, or even impossible in the near term, to return to the high level of employment achieved before the pandemic.”

The tight pre-pandemic labor market brought some people out of retirement, and economists say that could happen again if infections keep dropping and wages keep rising.

• How long until women’s employment recovers?

School reopenings were predicted to bring waves of women back to the workforce, but that has yet to happen and may not, according to the Brookings Institution.

Tracking how long it takes those women to get back to work is “going to be a very important focus of policymakers over the next six months,” said Joe Brusuelas, chief economist for consulting firm RSM.

If a large share find jobs in that time, that could lift the labor supply and ease wage pressures, he said. If not, then expectations for workforce recovery may drop and wage pressures could persist.

• Are savings keeping people home?

Savings accumulated during the pandemic as consumers reduced spending, received stimulus checks and benefited from a federal pause on student loan and mortgage payments. This perhaps gave job seekers room to hold out for the right position or to care fulltime for family longer. Those funds could soon run out now that enhanced unemployment benefits are gone and some forbearance programs are expiring, economists say.

As of September, households had saved about $2.5 trillion more than they would have if the pandemic had never happened, Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, estimates. Most of that was stashed away by higher-income households. Still, he estimates about $500 billion was saved by households in the 20-60 percent range of the income distribution, leaving those households with about $10,000 per person, which he projects will get spent down by the end of this year or early 2022.

Lower-income households, by contrast, have only about $1,000 saved on average, according to the JPMorgan Chase Institute. “The financial pressure to go back to work will be overwhelming,” Mr. Zandi said.

• How many people prefer to work for themselves?

The pandemic sparked a surge in filings for new businesses as people tried to capitalize on new trends, make ends meet as freelancers or take more control over their work.

That could help explain some of the worker shortage: More people are choosing to go it alone. It is too early to know how many new businesses will survive or how many jobs they might create.

Analysis from the Atlanta Fed and University of Maryland economist John Haltiwanger found many of the new businesses are likely to remain “non-employer” firms—one-person businesses run by people who are now self-employed. But the number of firms with a “high propensity” to generate jobs also increased.

• Will immigration rebound?

Immigration declined over the past several years under former President Donald Trump’s stricter policies and then restrictions imposed during the pandemic. Visas issued to work-eligible foreigners declined by 1.2 million during the pandemic, according to the Cato Institute.

That trend is reversing as infections drop and restrictions are loosened. The number of immigrant workers could rise by between 250,000 to 500,000 next year from current levels, Julia Coronado, president of MacroPolicy Perspectives and a former Fed economist, said during a recent webinar.

The decline in immigration could allow labor market conditions to stay tight even without a full return to pre-pandemic employment levels, said Jesse Edgerton, a senior economist at J.P. Morgan. That means wages could continue to grow for some jobs, pulling more people off of the sidelines and boosting labor force participation.

- Real Truth Magazine Articles

- PROPHECY

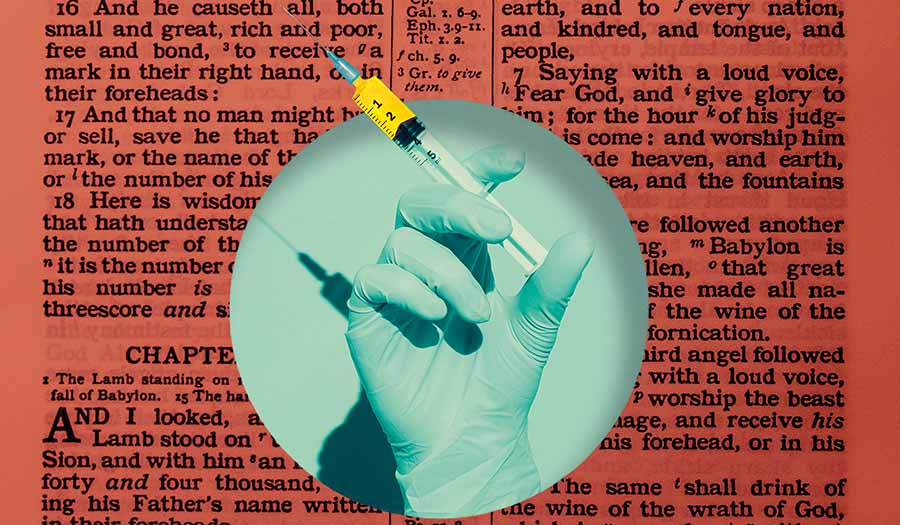

COVID Vaccines: The Mark of the Beast?

COVID Vaccines: The Mark of the Beast?

Other Related Items:

- Supply Chain Disruption: Is the Worst Over?

- What’s Behind the Migrant Crisis at the Belarus-Poland Border