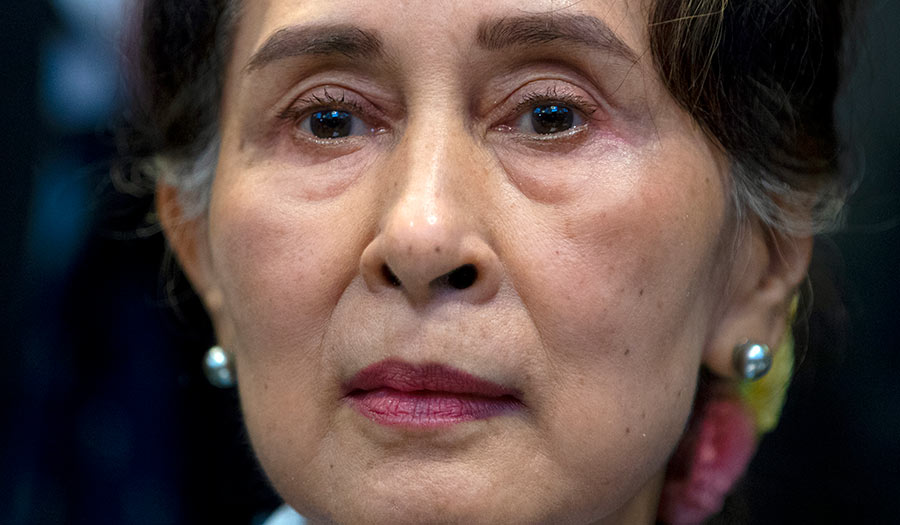

AP/Peter Dejong

AP/Peter Dejong

World News Desk

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowBANGKOK (AP) – Aung San Suu Kyi, the civilian leader of Myanmar who was ousted in a de facto coup this year, was convicted of incitement and another charge Monday and sentenced to four years in prison—in a trial widely criticized as a further effort by the country’s military rulers to reverse the democratic gains of recent years.

Hours later, state television reported that her sentence had been reduced to two years in an amnesty and indicated she would not serve it in prison but instead where she is currently being detained.

The convictions serve to cement a dramatic reversal of fortunes for the Nobel Peace laureate, who spent 15 years under house arrest for resisting the Southeast Asian nation’s generals but then agreed to work alongside them when they promised to usher in democratic rule.

Monday’s verdict was the first in a series of cases brought against 76-year-old Ms. Suu Kyi since her arrest on February 1, the day the army seized power and prevented her National League for Democracy party starting a second term in office.

If found guilty of all the charges she faces, Ms. Suu Kyi could be sentenced to more than 100 years in prison. She is being held by the military at an unknown location.

The court earlier offered a 10-month reduction in the sentence for time served, according to a legal official, who relayed the verdict to The Associated Press and who insisted on anonymity for fear of being punished by the authorities. The state TV report did not mention any credit for time served.

The army seized power claiming massive voting fraud in the November 2020 election, which Ms. Suu Kyi’s party won in a landslide. Independent election observers did not detect any major irregularities.

Opposition to the takeover sprang up almost immediately and remains strong, with armed resistance spreading after the military’s violent crackdown on peaceful protests. The verdict could inflame tensions even further.

The cases against Ms. Suu Kyi are widely seen as contrived to discredit her and keep her from running in the next election since the constitution bars anyone sent to prison after being convicted of a crime from holding high office or becoming a lawmaker.

Rights groups deplored the verdict, with Amnesty International calling it “the latest example of the military’s determination to eliminate all opposition and suffocate freedoms in Myanmar.”

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, said the trial was just the beginning of a process that “will most likely ensure that Suu Kyi is never allowed to be a free woman again.”

Ms. Suu Kyi is widely revered at home for her role in the country’s pro-democracy movement—and was long viewed abroad as an icon of that struggle, epitomized by her 15 years under house arrest.

But since her release in 2010 and return to politics, she has been heavily criticized for the gamble she made: showing deference to the military while ignoring and, at times, even defending rights violations—most notably a 2017 crackdown on Rohingya Muslims that rights groups have labeled genocide.

While she has disputed allegations that army personnel killed Rohingya civilians, torched houses and raped women and she remains immensely popular at home, that stance has tarnished her reputation abroad.

The incitement charge centered on statements posted on the Facebook page of Ms. Suu Kyi’s party after she and other party leaders were detained by the military. She was accused of spreading false or inflammatory information that could disturb public order. In addition, she was accused of violating coronavirus restrictions for her appearance at a campaign event ahead of the elections last year.

- Real Truth Magazine Articles

- GEOPOLITICS

Myanmar on the Edge – Should We Intervene?

Myanmar on the Edge – Should We Intervene?

More on Related Topics:

- In Cambodia, Thousands Flood Out of Scam Compounds and Find Little Help

- Syrian Government, Kurds Agree to International Deal in ‘Historic Milestone’

- How Syria’s Government Has Redrawn the Map with Advances Against the Kurds

- Explainer: What’s Happening in Yemen, and Why Are Saudi Arabia and the UAE Involved?

- Civilians Flee Aleppo as Clashes Between Syrian Government and Kurdish Forces Escalate