Suggested Reading:

America and Britain in Prophecy

America and Britain in Prophecy

Calls in Scotland for independence seem to be growing louder. Could this mean the end of the UK?

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowFrom a group of islands approximately 100,000 sq. mi. (250,000 sq. km.) in size reigned the world’s largest empire: the United Kingdom. Culminating in the 19th century under Queen Victoria, the British Empire controlled approximately one-quarter of the world’s land, resources and population.

The Union Flag (“Union Jack”) and the empire that it represented is considered controversial in today’s politically correct society.

On one hand, its legacy is widespread in legal, military, education and government systems, and in economic practice. Its image dominates sports (cricket, rugby, and football/soccer), and symbolizes the global spread of the English language.

On the other hand, to some, its effigy reflects an empire of slavery and racism, brutality and aggression, pride and arrogance.

But, thousands of years earlier, the empire was foretold. In the book of Genesis, God told Jacob, whom He renamed Israel, to “be fruitful and multiply; a nation and a company of nations shall be of you, and kings shall come out of your loins…” (35:10-12).

Many have understood that this “company of nations” refers to the British Empire and/or the Commonwealth of Nations (formerly the British Commonwealth).

And yet, God also warned that those blessings would be removed for national disobedience (Read Leviticus 26). Since the two world wars, Britain has been in decline. Despite remaining a significant military power, its armies have lost the prestige they once held.

The United Kingdom—which consists of the British isle states of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland—has undergone its own decline.

In 1922, Ireland split into two states, one declaring independence and becoming the Republic of Ireland; the other remaining a part of the UK, becoming Northern Ireland.

In 1998, Scotland was granted the resumption of its own parliament in Edinburgh.

In recent months, calls for Scottish independence have increased (they were also somewhat popular during the 1970s).

Could this spell the end of the United Kingdom?

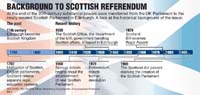

The UK’s origins trace back to the early 10th century AD, when the Anglo-Saxon king Athelstan (also spelled Aethelstan or Ethelstan) brought together under one rule several neighboring Celtic kingdoms. Crowned at Kingston on September 4, 925, Athelstan’s codes of law decreed stern efforts to suppress theft and corruption, while at the same time intending to comfort the destitute. Both his charters and his silver coins carried the proud title Rex totius Britanniae (“King of all Britain”).

During the centuries that followed, the kingdom slowly expanded. Keep in mind that this was interspersed with periods of infighting among the English, Scottish and Irish peoples, and various clans within each. In addition, Scandinavian peoples, or Vikings, continued to invade and ultimately gained control for a time (994-1042), followed by the Normans, whose most famous ruler was William the Conqueror (William I, 1066-1087).

The Scottish Office, Harenberg Encyclopedia, Encylcopaedia Britannica; MCT

The Scottish Office, Harenberg Encyclopedia, Encylcopaedia Britannica; MCTAn interesting common element during these various early periods of UK history is not only the almost constant power struggle between various peoples and countries but the UK’s resistance to the religious authority of Rome, despite strengthening economic ties with continental Europe.

For example, King William I and Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, worked together and resisted Pope Gregory VII’s claim to papal supremacy. The king even decreed that no pope was to be recognized in England without his consent, no papal letter was to be received, no Roman church council was to legislate, and no English baron or royal official was to be excommunicated.

King John (1199-1216) also fought with Rome over the choice of archbishop, which eventually resulted in the king’s excommunication, and allowed his administration to confiscate all revenues of sees that had been vacated by bishops in exile.

The most famous account of England opposing Rome was during King Henry VIII’s reign (1509-1547). When he was denied a marriage annulment, Henry eventually enacted the Act of Succession of March 1534, forcing his English subjects to accept his new marriage, and the Act of Supremacy, which formally severed all financial and constitutional ties with Rome. It was also at this time that the Acts of Union of 1536 and 1542 brought Wales, another enclave of Celtic kingdoms in the island’s southwest, to unity with England.

Following the Glorious Revolution (1688-1689), Scotland, which had been ruled by the English monarchy since 1603, was formally joined with England and Wales by the Acts of Union in 1707, under Queen Anne (1702-1714). This marked the beginning of the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

Though Ireland was under English control during the 1600s, it was the Act of Union of 1800 that united Great Britain and Ireland—the United Kingdom was now complete. The timing was near perfect, as economic growth and prosperity quickly increased following the American Revolution. In addition, the effects of the beginnings of the (first) Industrial Revolution were making a significant impact. From 1794 to 1814, annual British exports doubled from £22 million to £44 million. Population growth also exploded: By 1790 it had reached 9.7 million; by 1811, 12.1 million; and by 1821, 14.2 million. By the latter date, an estimated 60% of Britain’s population was 25 years of age or below. By the 1850s, the population was over 20 million. The United Kingdom and the British Empire it ruled was at its peak, possessing “the gate [seagates] of his enemies” (Gen. 22:17). This included the Suez Canal, the Straits and Island of Gibraltar, Cape of Good Hope, the Straits of Hormuz, Singapore, Malta and Hong Kong—dominating world commerce and trade.

Ireland was the shortest-lasting member state of the United Kingdom, with increasing differences among unionist and republican, as well as Protestant and Catholic, forces during the late 1800s and early 1900s. This culminated with the Anglo-Irish treaty of December 6, 1921, which created the independent Irish Free State. The northeastern area, known as Northern Ireland, remained a part of the UK.

By the late 1940s, Irish politics pushed toward unification and independence, leading to the Republic of Ireland Act of 1949. Britain recognized Ireland’s new status, but unity with Northern Ireland could take place only with mutual political consent. During the 1950s and 60s, the governments faced Irish Republican Army (IRA) attacks on British army outposts along the northeastern border. Various political visits, assassinations and agreements, all in an attempt to secure peace, continued for several decades. Annual Protestant and Catholic marches became typical flashpoints for violence.

In 1993, the Irish and British governments signed a joint peace initiative called the Downing Street Declaration. The next year, the IRA declared a cease-fire, increasing optimism. But by 1996 its bombing campaign resumed. Two years later, Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern played a significant role in brokering the Belfast (or Good Friday) Agreement. This included the creation of a Northern Ireland Assembly, established some north-south political structure, and removed the claim to Northern Ireland from Ireland’s 1937 constitution. That same year, 94% of voters in Ireland and 71% in Northern Ireland approved the agreement. Despite intermittent progress, including the IRA’s renouncement of armed struggle in 1995, power sharing has become a reality in Northern Ireland. Earlier this year, the British army ended its nearly four-decade long mission there.

Scotland has “long refused to consider itself as anything other than a separate country, and has bound itself to historical fact and legend alike in an effort to retain national identity” (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

The United Kingdom controlled most of the seaports and areas of wealth around the world. Throughout the 1900s, the larger colonies gained independence, shrinking the empire on which “the sun never set.”With the discovery of oil in the North Sea in the 1970s, the Scottish National Party (SNP) made some political gains. The independent mindset bore symbolic fruit with the 1996 return of the Stone of Scone (or Stone of Destiny) from London to Edinburgh. Elements of history indicate that this is the same stone that Jacob slept on in Genesis 28; the one that the prophet Jeremiah brought to the British Isles (ca. 700 B.C.). Irish, Scottish and English kings have been coronated upon this stone ever since.

In 1997, the Labour government called for a referendum on the creation of a Scottish Parliament. It passed with support of more than 74% of voters, and in May 1999, its first members were elected. The SNP staged a historic upset in the 2007 elections, winning the most seats (47 of 129). Its leader, Alex Salmond, was subsequently named the First Minister of Scotland.

Mr. Salmond has announced plans for a referendum to be held in 2010, aimed at securing independence for Scotland for the first time in 300 years. The referendum date gives the SNP “plenty of time to demonstrate competence. I’m committed to a new chapter in Scottish politics, one that’s written by the people,” Mr. Salmond said, launching what he called a “national conversation” on the referendum proposal (Bloomberg).

According to Mr. Salmond, the status quo is no longer an option. If he is proven right, this would present UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown (who is also Scottish) with a serious challenge to his opposition to Scottish independence.

Des Browne, the Secretary of State for Scotland, warned against allowing “the cleverness of Alex Salmond and the SNP to dress this up as anything other than what it is—the central theme of the document is about breaking up Britain.”

He added, “This is what Alex Salmond is about. People of Scotland identify that and they don’t support it. This was tested recently in an election in Scotland and 65% voted for parties who want to preserve a United Kingdom.”

Opinion polls have also consistently revealed that Scots want more power for their Parliament, yet are wary of full independence.

The British Empire no longer exists. Great Britain is no longer “great.” And the United Kingdom appears to be no longer united and headed toward its end.

In fact, the UK will indeed cease to exist in its current form. To learn more, read the book America and Britain in Prophecy.