Getty Images

Getty Images

Article

Those who weathered the Great Depression are famed for their work ethic, tenacity, ingenuity and character. What about the 1930s caused this group to later be dubbed the “Greatest Generation”?

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowThe 1930s are often described as the worst of times. Encyclopaedia Britannica calls the period “the harshest adversity faced by Americans since the Civil War.” Author Timothy Egan titled a book on the 1930s Dust Bowl The Worst Hard Time.

Those who grew up during the 1930s are markedly different. They have been called the Greatest Generation. Commonly, this age group is viewed as tougher, more weathered. They are known as hardworking and obstinate. This is a generation that seems to make true the old saying “What does not kill me, makes me stronger.”

And while the above description is a generalization, they have known hard times—war, famine, disease—and have conquered them.

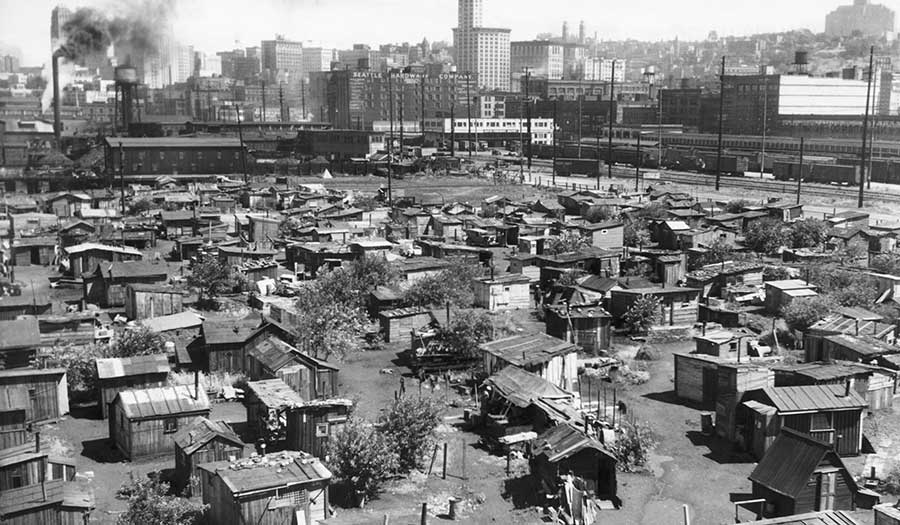

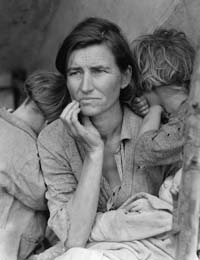

It can be difficult to see what about the 1930s could change an entire generation. For most today, the words “Great Depression” may at best bring grainy black and white photographs to mind. Images of the weathered face of a mother with worried creases in her forehead, her children burying their faces in her shoulders; or perhaps it summons the movie-set recreation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. If asked, perhaps a few would respond with a simple—“Black Thursday” or “The New Deal,” with others perhaps saying “Dust Bowl.”

But overall, if pushed, most today cannot truly say what those days were like, with the images and stories being relegated to Hollywood or mere footnotes in history. The number of those who grew up during the 1930s is slowly dwindling, and with them, the memories and lessons learned. What about this event made an entire generation be called the “Greatest”?

Something Is Missing

In general, Americans live privileged lives, lives of abundance. Even the poor in the United States have it better than the majority of the rest of the world.

Americans have had it good, and for quite some time. An entire generation has grown up with nothing wanting, with no sustained hardships. In the past, these trials have come in the form of the Civil War or World War II, events requiring sustained periods of lifestyle change and sacrifice.

This is not to say hardships never occur. The cases of September 11 attacks, the Hurricane Katrina disaster and families losing loved ones in Iraq are all tragic, but do not quite reach the same level of widespread hardship seen in the past.

One can seem to make a good case that it is positive that children and now adults have grown without being exposed to what can be called lean times, a wartime draft, disease epidemics or severe recessions. It can seem good to avoid periods of adversity.

Yet something is missing when one grows up without periods of hardship. And those who lived through the Great Depression can show why.

From Crash to Crippling Depression

Leading up to the depression was a period of wild growth—the Roaring Twenties! A housing boom, stock boom, industry boom—the nation was exploding with expansion.

Most did not see it coming.

“Black Thursday,” October 24, 1929, is generally noted as the start of the Great Depression. A stock market price bubble burst, worsened by panicked financiers liquidating their holdings. The stocks soon were hardly worth the paper on which they were printed.

Yet the average citizen still looked optimistically to the coming decade. They thought: How could a bunch of wealthy investors losing their money affect me? The following months proved how wrong they were.

Perhaps the worst hit by Black Thursday were middle class investors. Between 15–25 million Americans owned stocks or had family members who did. These families often lost every cent of their savings in the crash, which also meant these former investors would not be there to put money back into the market.

With time, banks began to fail. During 1930 at least 744 banks failed, with a total of 9,000 banks failing before the decade closed. Only a little over three years after the crash, $140 billion of depositors’ cash was lost.

Businesses began to go under; factories closed. Jobs began to be scarce for the approximately 122 million Americans. In 1929, a little less than 3 million citizens did not have a job; 4 million in 1930; 8 million in 1931; and by 1932—12.5 million Americans were unemployed. This meant one quarter of the nation’s families had no working parent.

November of 1929 saw industrial production drop 7%. In December, private construction work dropped 43%.

The effects of the crash rippled outward from America: the economies of Britain, Germany and other European nations were especially affected.

It soon became apparent that America would not immediately bounce back.

Farms too were hit. Crop prices plummeted. Wheat and cotton rotted in the field because it cost more to harvest than the price that would be paid. Newsreel footage caught dairy farmers dumping milk on the side of the road, hoping in vain to increase prices.

The economic effects of bank failures and price drops coupled with another scourge plaguing the Great Plains: drought.

The High Plains of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico had seen a wheat boom during World War I. The land was worked non-stop, only halted with the price drop and lack of rainfall.

With their last crop failing to bring in a substantial profit, farms now saw only scorching heat and little rain.

“The Worst Hard Time”

When looking for what was learned by the Greatest Generation, the mere facts of history above do little to explain the hardships that were weathered and what the conditions were truly like.

The following is an example of those who perhaps suffered the worst during the 1930s. As you read, put yourself in their shoes and consider how such an event would change you. Remember the conditions described below for some lasted ten long years!

With the economic uncertainty, coupled with drought and poor agricultural practices, farming families were most affected by the depression. Yet a worse terror loomed.

The parched and exposed topsoil began to blow away. Sweeping winds sifted the dirt, picking up only the finest particles. Billowing and growing higher, feeding on the dry earth below, dust storms would tear through towns and houses. The fine powder seeped through every crack in the homes and buildings. Inside, dust was everywhere, on everything, in everything. Day or night, they could not escape its suffocating presence.

Outside, the winds could exceed hurricane strength. The storms darkened the sky often blotting out the sun. If one did not have a tether or fence to follow he would be lost.

Residents coughed up dirt. For some, it soon gave way to a form of silicosis, a disease contracted by seasoned coal miners, and an ailment named dust pneumonia that killed many elderly and children.

Some storms picked up enough topsoil to blanket cities as far east as Washington, D.C. and New York City. Experts estimate 850 million tons of topsoil were removed in 1933 alone.

Dust Bowl residents were told to wear dampened masks, which worked for a short time until they were muddied and virtually useless.

And the “black blizzards” brought more troubles. Birds and predators fled due to drought and the constant storms, leaving increasing hordes of grasshoppers that ate anything green left. They also would eat through the handles of hoes and shovels. The lack of natural predators led to an infestation of jackrabbits—thousands quickly multiplying to more thousands that scoured the countryside.

The storms begat other strange occurrences: Static from the blasts of sand caused barbed wire fences and windmills to crackle with electricity. The charge was strong enough to stop the car engines of those caught driving in one of the dusters.

Soon, the only thing left to eat was pickled tumbleweed and rabbit meat.

In the book The Worst Hard Time, Timothy Egan detailed a true life account of a family coping with the dust: “The family…had tried to seal their home, stuffing rags into wall cracks, gluing strips of flour paste-covered paper around the door, taping windows and then draping damp gunnysacks over the opening. Wet bed sheets were hung against the walls as another filter. But all the layers of moist cloth and flour paste could not keep the wind-sifted particles out.”

“The plow…was almost completely buried. Going to the outhouse was an ordeal, a wade through shoulder-high drifts, forced to dig to make forward progress.”

Everyone was always coughing, eyes red and itching.

Many left. Families would heap all their belongings onto their automobiles and drive. Most headed to California, in search of work.

By the time they arrived, they were nearly starving. Fathers would take any job so as not to see their children go hungry.

In California, the Dust Bowl refugees found only the squalor of worker camps. Parents watched as their children died of malnutrition. Only those with the strongest will were not broken.

But, despite the horrid conditions, many weathered all ten years of the dust storms and drought, even plowing the land once again when the rains returned.

Is Sorrow Better Than Laughter?

Any number of stories from the 1930s could paint a picture of the hardships of the times. The Great Depression saw wealthy businessmen, who days earlier had everything, but now thought their only option was leaping from a skyscraper window. It saw sturdy men cry because they had no way to feed their family. Oklahoma families toughed out ten years of dust-filled homes and dirt-clogged lungs. African-Americans in Harlem lost their jobs first, simply for the color of their skin—which later lead to riots. Dust Bowl refugees watched their children die of malnutrition in California.

Yet the question remains, what about these trying times built the character of the Greatest Generation?

Hard times often lead people back to religion, to get on their knees and pray for help or merely deliverance. And in fact, the existence of hardships is explained in the Bible, but the answer may not be as expected: “In the day of prosperity be joyful, but in the day of adversity consider: God also has set the one over against the other, to the end that man should find nothing after Him” (Ecc. 7:14). Good times are set against bad times. The one follows the other in a continual cycle.

Notice this verse points out that God is the one who “has set the [good/bad times] over against the other.” Why?

Verses 2 and 3 of Ecclesiastes 7 reveal more of God’s purpose in permitting suffering: “It is better to go to the house of mourning, than to go to the house of feasting: for that is the end of all men; and the living will lay it to his heart. Sorrow is better than laughter: for by the sadness of the countenance the heart is made better.”

Though these passages may be shocking, they prove God places great importance on building character. Through trying times, “the heart is made better.”

The apostle Paul also showed that after a life of severe periods of hardship he learned “in whatsoever state I am, therewith to be content” (Phil. 4:11).

In verse 12 he continued, “I know both how to be abased, and I know how to abound: everywhere and in all things I am instructed both to be full and to be hungry, both to abound and to suffer need.

Paul learned that through days of adversity the heart truly is made better. The Greatest Generation is a near-textbook example of this. (For more information, read our article “Why Does God Allow Suffering?”)

Americans have experienced abundance for quite some time, which means we are due for harder times. Will you give up during these coming days of adversity? Or trudge forward, allowing the trying times to temper and change you for the better?

- Real Truth Magazine Articles

- ANALYSIS

“Days of Adversity”: What Unprecedented Wealth Reveals About a Nation’s Character

“Days of Adversity”: What Unprecedented Wealth Reveals About a Nation’s Character