Olivier Morin/AFP/Getty Images

Olivier Morin/AFP/Getty Images

Article

At the climate summit in Denmark, United Nations members put aside recent debate over whether or not climate change is true, convening instead with the goal of securing “hope” for future generations. But their noble intentions and high expectations missed what is truly needed to save the world.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

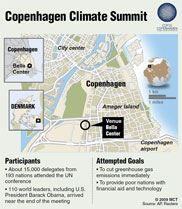

Subscribe NowAs delegates representing 193 nations kicked off the 15th United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark—considered by many leaders to be the “last chance” for planet Earth—the world waited breathlessly, hopeful for a future-altering outcome.

Though controversy regarding the credibility of climate change data has filled recent headlines, the conference, considered the most important summit since the end of World War II, proceeded as planned.

Attila Kisbenedek/AFP/Getty Images

Attila Kisbenedek/AFP/Getty ImagesThe Scandinavian city came to a standstill in preparation for the highly anticipated gathering, also known as COP15, with more than 40,000 demonstrators clamoring to make their voices heard in hopes of saving the planet and its inhabitants from destruction at their own hands.

Buses could barely make their way through the bedlam of crowded streets as protestors’ voices echoed warnings of Earth’s demise between the city’s 18th-century stone buildings. Wearing outlandish costumes, waving brightly colored banners and shouting catchy slogans, demonstrators voiced their opinions in the streets of what Denmark’s Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen and Copenhagen’s mayor, Ritt Bjerregaard, renamed “Hopenhagen” for the two-week summit.

Demonstrators, with heads shaved in protest of climate change, toted posters bearing the words, “System Change Not Climate Change,” while others danced to club music from nearby DJ booths or formed conga lines.

Speakers, warning of what they believe is Earth’s imminent downfall, elicited wild cheers from their audiences. “We are peaceful, what are you?” a protestor standing on a platform shouted to a group of riot police, several of whom turned their backs and clutched their batons.

The raucous, Carnival-like atmosphere surrounding the Bella Center, where the conference was held, included a drumline following a Jewish man sounding a shofar—activists rolling a giant globe down the center of the road—a moment of silence in a mock cemetery dedicated to Earth—a crowd shouting, “One solution, trade pollution”—even dozens of out-of-place Iranian students loudly protesting against the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

STF/AFP/Getty Images

STF/AFP/Getty Images

The meeting was the fifth to convene regarding the 1997 signing of the Kyoto Protocol. This legally binding treaty aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for industrialized nations (excluding most developing countries, such as China and India) by an average of five percent against 1990 levels over the five year period from 2008-2012.

The UN Framework on Climate Change (UNFCC), a sector of the UN, which attempts to stabilize the level of harmful greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, supported the document, as did panelist recommendations from the UN-appointed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The panel’s conclusions have led many policymakers to accept that manmade climate change is a scientific fact.

At its inception, the Kyoto Protocol was hailed as a historic step toward combating the possible effects of proposed manmade climate change. Since its signing, leaders have continued to work toward creating a more far-reaching solution.

As the protocol expires in 2012, countries which ratified the agreement have until that time to devise a new treaty, which includes a goal of keeping the global temperature increase below two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) to prevent potential destructive climate patterns.

Whether or not climate change is real or imagined, conference leaders desired to positively impact Earth’s future.

The gathering of heads of state and non-governmental organizations believed they could do just that—yet something was lacking.

Quiet Chaos

Despite the hype and unprecedented political momentum leading up to the conference, a dark cloud overshadowed “Hopenhagen” from the start: under UN rules for climate change talks, any agreement requires unanimous approval of all 193 nations. This tall order has hindered nearly every climate talk since the Kyoto Protocol.

Jeff J. Mitchell/Getty Images

Jeff J. Mitchell/Getty Images Liselotte Sabroe/AFP/ Getty Images

Liselotte Sabroe/AFP/ Getty ImagesYvo de Boer, the executive secretary of the UNFCC, warned in the opening ceremony that delegates must act now as the “clock has ticked down to zero.”

“The time for formal statements is over,” he said. “The time for restating well-known positions is past.”

The COP15 introductory video made this “last chance” all the more urgent: a little girl dreaming of a world overcome with meteorological torments quietly begs those attending the summit, “Please, help the world.” The four-minute sequence ended with the phrase, “We have the power to save the world. Now.”

But the reality of the democratic UN system soon set in. Delegates began, one by one, to deliver rhetoric-laden speeches, reiterating the well-known positions of their nations.

On day three, the talks heated up. A representative for the South Pacific island nation of Tuvalu called for an enforceable agreement instead of the non-binding “political agreement” that had been expected for weeks. His proposal included aid for developing nations hit by changing weather patterns. In addition, several developing countries insisted wealthier nations owed them climate reparations.

A few Western nations countered that large developing nations such as India and China must make cutbacks on carbon emissions for any agreement to be worthwhile.

Halfway through the conference, violence erupted at a rally attended by tens of thousands of protesters demanding a binding treaty. Nearly 1,000 people were detained after the windows of two historic buildings were smashed with cobblestones. Police also arrested several youth who violated Denmark’s laws of either concealing their faces in public or carrying pocket knives.

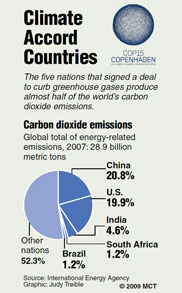

It seemed the confusion outside was echoed in the quiet chaos inside, as the conference crumbled into a finger-pointing match, with China and the United States at the core of the debate. China rebuffed any international monitoring of its emissions levels; the U.S. rejected any agreement that did not allow transparency for China’s actions.

China’s top climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua stated, “Given the fact that developed countries have done nothing but empty talk, they have no right to make further requests” (Forbes).

America’s response? “With respect to our emissions, it’s true our emissions have gone up since 1990,” U.S. Special Envoy for Climate Change Todd Stern said, adding, “the country whose emissions are going up, dramatically, really dramatically is China.” He also said that without developing economies such as China (the world leader in carbon emissions) doing their part, talks were useless.

On the second Monday, poorer nations staged a walkout protest, demanding more aid from the developed world to combat climate change, a move that temporarily shut down discussions.

Lumumba Di-Aping, chief negotiator for the G77, a group of developing nations, explained reasons for the walkout to BBC Radio 4. “It has become clear that the Danish presidency—in the most undemocratic fashion—is advancing the interests of the developed countries at the expense of the balance of obligations between developed and developing countries.”

By the start of week two, as world leaders began gathering in the Danish capital, progress was minimal.

“There is no time left for posturing or blaming,” United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a New York City press conference, before leaving for Copenhagen. “If everything is left to leaders to resolve at the last minute, we risk having a weak deal or no deal at all, and this will be a failure of potentially catastrophic consequences.”

Consensus Out of Confusion

Upon arrival, world leaders inherited a mess from a week of political infighting, disunity and blame-shifting—with only four days to turn the summit around.

But a few days later, hope seemed to return to “Hopenhagen.” Leaders felt they had to reach an agreement.

Working overtime, meetings went nonstop: official speeches, closed-door negotiations and lunchtime discussions took place, but to no avail.

On the final day of the conference, The New York Times declared, “Confusion reigns at the summit.” The paper described the scene: “Versions of draft negotiating texts are flying around the Bella Center. With only minimal information trickling out of the leaders’ meetings, rumors are ruling the conference. Aid groups wondered if China and India had walked out. The London Guardian passed on speculation that U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon had asked leaders to stay until tomorrow to secure a deal, but U.N. spokeswoman Marie Okabe said it is untrue.”

At the last minute, the conference produced the Copenhagen Accord—a bare-bones three-page document.

Some of the stipulations of the non-binding accord agreed upon by the U.S., China, India, Brazil and South Africa included: (1) stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations by limiting any manmade global temperature rise to below two degrees Celsius, (2) enhancing long-term cooperative action to combat climate change, and (3) giving $30 billion in aid to developing nations during the next three years to help poor countries combat the effects of climate change.

In the end, the UN itself decided it would “take note” of the accord—meaning it would merely acknowledge its existence—but not adopt it.

Following the difficult talks, many concluded that they would “take what they could get,” with the The Economist stating the common sentiment that it was better to reach “a suboptimal deal rather than none at all.”

Just 12 days after the opening film declared: “We have the power to change the world,” the world was left disenchanted.

Dashed Hopes

For those convinced that global warming exists, is manmade and is a present threat to the planet, the summit was considered Earth’s “last chance.” Yet world leaders were unable to devise a viable solution. Governments were powerless to stop what some have termed the greatest crisis of our time.

With disappointment resulting from the Copenhagen summit, should man give up?

Many feel the UN climate change conference system itself is at fault, saying there needs to be a stronger core governmental system to address the potential problem.

“The flawed Copenhagen outcome demonstrated the ‘underlying weakness’ in the United Nations climate process, said Andrew Light, coordinator of international climate policy at the Center for American Progress. ‘We need to start investigating other options, or at a minimum start using some alternative forums,’ he said, suggesting the G20 and the Major Economies Forum” (Reuters).

Last Chance?

All people yearn for a governmental system that can “solve every problem related to overpopulation, pollution, and production, procurement and distribution of food and water.”

A government that “will involve a complete change in entire weather patterns around the earth,” in which “clear water will be available—and in abundance—in all parts of the world.”

This soon-coming supergovernment, as detailed above from David C. Pack’s book Tomorrow’s Wonderful World – An Inside View!, will come to pass! Read this book to understand the effects of this government—and the hope it offers to a world that has had its “last chance.”

More on Related Topics:

- Why Freezing Rain Has Millions at Risk of Losing Power—and Heat

- Firefighters Face Attacks, Drones and Arsonists While Battling Deadly Blazes in Chile

- ‘It’s Not Safe to Live Here.’ Colombia Is Deadliest Country for Environmental Defenders

- ‘Everything Destroyed’ as Indonesia’s Aceh Grapples with Disease After Floods

- A Drying-Up Rio Grande Basin Threatens Water Security on Both Sides of the Border