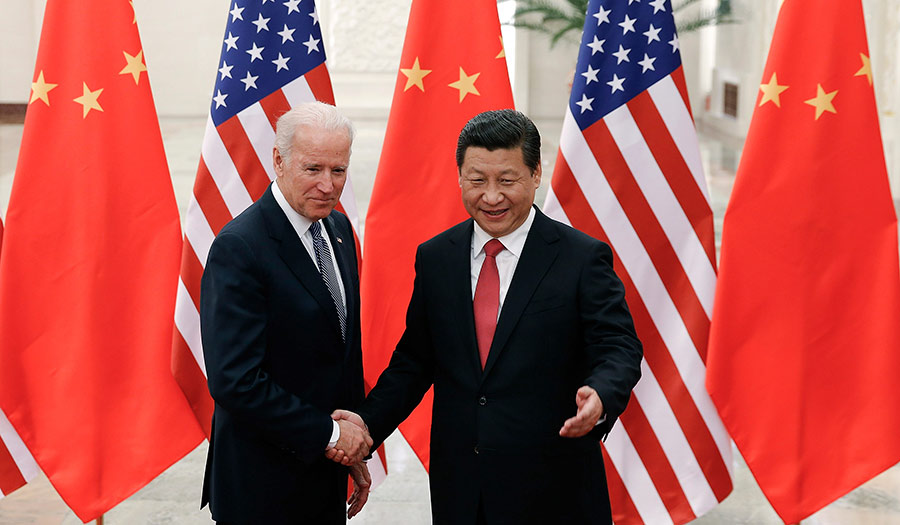

AP/Lintao Zhang

AP/Lintao Zhang

World News Desk

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowTOKYO (AP) – As Asia comes to terms with the reality of a Joe Biden administration, relief and hopes of economic and environmental revival jostle with needling anxiety and fears of inattention.

From security to trade to climate change, a powerful U.S. reach extends to nearly every corner of the Asia-Pacific. In his four years in office, President Donald Trump shook the foundations of U.S. relations here.

Now, as Mr. Biden looks to settle tumultuous domestic issues, there is widespread worry that Asia will end up as an afterthought. Allies will go untended. Rivals—and especially China—will do as they like.

Here is a look at how a Biden White House will play out in one of the world’s most important and volatile regions.

China

Mr. Biden will likely look here first.

The two nations are inexorably entwined, economically and politically, even as the U.S. military presence in the Pacific chafes against China’s expanded effort to have its way in what it sees as its natural sphere of influence.

Under Mr. Trump, the two rivals engaged in a trade war. A Biden administration could have a calming effect on those frayed ties, according to Alexander Huang, a strategic studies professor at Tamkang University in Taipei and a former Taiwanese national security official.

“I’d expect Biden to return to the more moderate, less confrontational approach of the Obama era toward China-U.S. relations,” he said.

Greater outreach to China could prompt Washington to play down its support for Taiwan, which China claims as its own territory, without necessarily reducing U.S. commitment to ensure the island can defend itself against Chinese threats, Mr. Huang said.

Retired chemical engineer Tang Ruiguo echoed a view shared by many in China of an unstoppable U.S. decline from global superpower status. “No matter who is elected, I feel the United States may go into turmoil and unrest and its development will be affected,” Mr. Tang said.

The Koreas

Say goodbye to the summits.

Mr. Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un went from threats of war to three unprecedented sit-downs, which, though high-profile media events, did not succeed in ridding the North of its banned nuclear-tipped long-range missiles.

Mr. Kim must now adjust to a man his propaganda services once condemned as a “rabid dog” that “must be beaten to death.”

Mr. Biden, for his part, has called Kim a “butcher” and “thug,” and said Mr. Trump had gifted a dictator with legitimacy with “three made-for-TV summits” that produced no disarmament progress.

Mr. Biden has endorsed a slower approach built from working-level meetings and said he would be willing to tighten sanctions on the North until it takes concrete denuclearization steps.

North Korea, which has yet to show any willingness to fully deal away a nuclear arsenal that Mr. Kim may see as his strongest guarantee of survival, prefers a summit-driven process that gives it a better chance of pocketing instant concessions that would otherwise be rejected by lower-level diplomats.

For South Korea, the new president will likely demonstrate more respect toward its treaty ally than Mr. Trump, who unilaterally downsized joint military training and complained about the cost of the 28,500 U.S. troops stationed in the South to defend against North Korea.

Japan

There is hope in Tokyo that Mr. Biden’s more progressive ecological policies will help Japanese green companies and that he will take a hard line on China, with which Japan is in constant competition.

But there is also worry.

Under Mr. Biden, “America cannot afford to take care of other countries, and it has to prioritize its own reconstruction,” said Hiro Aida, Kansai University professor of modern U.S. politics and history.

As Mr. Biden is consumed with his nation’s many domestic troubles, from racial unrest to worries about the economy, healthcare and the coronavirus, Japan could be left alone as China pursues its territorial ambitions and North Korea expands its nuclear efforts, according to Peter Tasker, a Tokyo-based analyst with Arcus Research.

India

Not much will change with the host of security and defense ties shared by India and the United States. But a Biden administration could mean a much closer look at India’s spotty recent human rights and religious freedom records.

Mr. Biden is also expected to be more critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalistic policies, which critics say oppress India’s minorities, according to Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program at the Washington-based Wilson Center.

More on Related Topics:

- North Korea’s Kim Again Threatens to Use Nuclear Weapons Against South Korea and U.S.

- Russia and North Korea’s Partnership

- Hamas and Fatah Agree to Form a Government. What Does It Mean and Who Are These Palestinian Groups?

- President Biden’s Withdrawal Injects Uncertainty into Foreign Policy Challenges

- What to Know About the NATO Military Alliance and How It Is Helping Ukraine