NASA via AP

NASA via AP

World News Desk

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

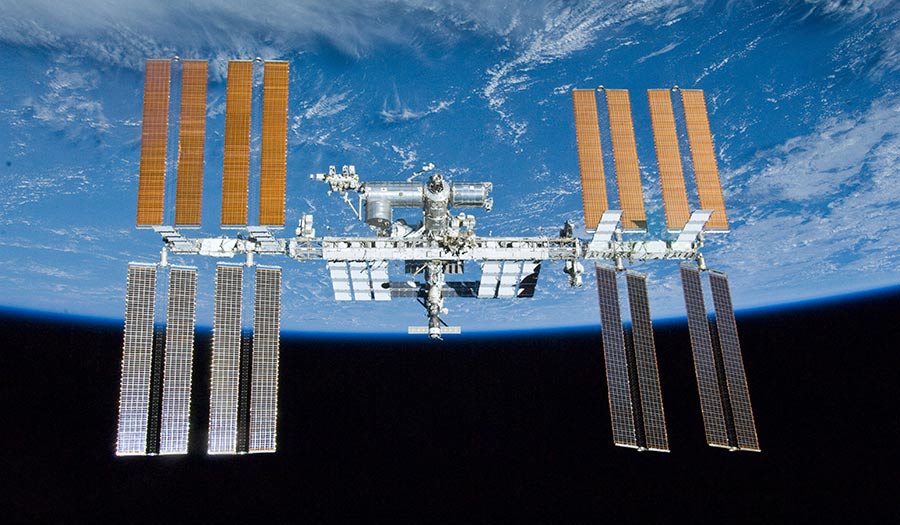

Subscribe NowCAPE CANAVERAL, Florida (AP) – The International Space Station was a cramped, humid, puny three rooms when the first crew moved in. Twenty years and 241 visitors later, the complex has a lookout tower, three toilets, six sleeping compartments and 12 rooms, depending on how you count.

November 2 marked two decades of a steady stream of people living there.

Astronauts from 19 countries have floated through the space station hatches, including many repeat visitors who arrived on shuttles for short-term construction work, and several tourists who paid their own way.

The first crew—American Bill Shepherd and Russians Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko—blasted off from Kazakhstan on October 31, 2000. Two days later, they swung open the space station doors, clasping their hands in unity.

Shepherd, a former Navy SEAL who served as the station commander, likened it to living on a ship at sea. The three spent most of their time coaxing equipment to work; balky systems made the place too warm. Conditions were primitive, compared with now.

Installations and repairs took hours at the new space station, versus minutes on the ground, Mr. Krikalev recalled.

“Each day seemed to have its own set of challenges,” Mr. Shepherd said during a recent NASA panel discussion with his crewmates.

The space station has since morphed into a complex that is almost as long as a football field, with eight miles of electrical wiring, an acre of solar panels and three high-tech labs.

“It’s 500 tons of stuff zooming around in space, most of which never touched each other until it got up there and bolted up,” Mr. Shepherd told The Associated Press. “And it’s all run for 20 years with almost no big problems.”

“It’s a real testament to what can be done in these kinds of programs,” he said.

Mr. Shepherd, 71, is long retired from NASA and lives in Virginia Beach. Mr. Krikalev, 62, and Mr. Gidzenko, 58, have risen in the Russian space ranks. Both were involved in the mid-October launch of the 64th crew.

The first thing the three did once arriving at the darkened space station on November 2, 2000, was turn on the lights, which Mr. Krikalev recalled as “very memorable.” Then they heated water for hot drinks and activated the lone toilet.

“Now we can live,” Mr. Gidzenko remembers Mr. Shepherd saying. “We have lights, we have hot water and we have toilet.”

The crew called their new home Alpha, but the name did not stick.

Although pioneering the way, the three had no close calls during their nearly five months up there, Mr. Shepherd said, and so far the station has held up relatively well.

NASA’s top concern nowadays is the growing threat from space junk. This year, the orbiting lab has had to dodge debris three times.

As for station amenities, astronauts now have near-continuous communication with flight controllers and even an internet phone for personal use. The first crew had sporadic radio contact with the ground; communication blackouts could last hours.

While the three astronauts got along fine, tension sometimes bubbled up between them and the two Mission Controls, in Houston and outside Moscow. Mr. Shepherd got so frustrated with the “conflicting marching orders” that he insisted they come up with a single plan.

“I’ve got to say, that was my happiest day in space,” he said during the panel discussion.

With its first piece launched in 1998, the 260-miles-high International Space Station already has logged 22 years in orbit. NASA and its partners contend it easily has several years of usefulness left.

The Mir station—home to Mr. Krikalev and Mr. Gidzenko in the late 1980s and 1990s—operated for 15 years before being guided to a fiery reentry over the Pacific in 2001. Russia’s earlier stations and America’s 1970s Skylab had much shorter life spans, as did China’s much more recent orbital outposts.

Astronauts spend most of their six-month stints these days keeping the space station running and performing science experiments. A few have even spent close to a year up there on a single flight, serving as medical guinea pigs. Mr. Shepherd and his crew, by contrast, barely had time for a handful of experiments.

The first couple weeks were so hectic—“just working and working and working,” according to Mr. Gidzenko—that they did not shave for days. It took a while just to find the razors.

Even back then, the crew’s favorite pastime was gazing down at Earth. It takes a mere 90 minutes for the station to circle the world, allowing astronauts to soak in a staggering 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets each day.

The current residents—one American and two Russians, just like the original crew—plan to celebrate Monday’s milestone by sharing a special dinner, enjoying the views of Earth and remembering all the crews who came before them, especially the first.

But it will not be a day off: “Probably we’ll be celebrating this day by hard work,” Sergei Kud-Sverchkov said Friday from orbit.

Massive undertakings like human Mars trips can benefit from the past two decades of international experience and cooperation, Mr. Shepherd said.

“If you look at the space station program today, it’s a blueprint on how to do it. All those questions about how this should be organized and what it’s going to look like, the big questions are already behind us,” he told the AP.

Russia, for instance, kept station crews coming and going after NASA’s Columbia disaster in 2003 and after the shuttles retired in 2011.

When Mr. Shepherd and his crewmates returned to Earth aboard shuttle Discovery after nearly five months, his main objective had been accomplished.

“Our crew showed that we can work together,” he said.

More on Related Topics:

- The Future of Energy?

- How Social Media Became a Storefront for Deadly Fake Pills

- Cyberattacks on U.S. Utilities Surged 70 Percent This Year, Says Check Point

- A Robot Begins Removal of Melted Fuel from the Fukushima Nuclear Plant. It Could Take a Century

- Explainer: Why South Korea Is on High Alert over Deepfake Sex Crimes