NASA

NASA

Article

It appears man’s footprints will grace the lunar surface once again—more than five decades after the first landing. What is motivating us to return?

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowIdealism can seem to border on lunacy—particularly when one does not have the means to accomplish a goal.

One could have thought this when U.S. President John F. Kennedy committed on May 25, 1961, to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth “before this decade is out.”

At the time he uttered those words, this goal sounded virtually impossible. “We didn’t have the tools or equipment—the rockets or the launchpads, the spacesuits or the computers or the micro-gravity food,” Smithsonian reported.

“And it isn’t just that we didn’t have what we would need; we didn’t even know what we would need. We didn’t have a list; no one in the world had a list. Indeed, our unpreparedness for the task goes a level deeper: We didn’t even know how to fly to the Moon. We didn’t know what course to fly to get there from here.

“And…we didn’t know what we would find when we got there. Physicians worried that people wouldn’t be able to think in micro-gravity conditions. Mathematicians worried that we wouldn’t be able to calculate how to rendezvous two spacecraft in orbit—to bring them together in space and dock them in flight both perfectly and safely.”

Thousands of concerns were laid on the table: A Cornell astrophysicist warned that lunar dust that had been isolated from oxygen could combust when brought back into a lunar module’s cabin. He also speculated that a spacecraft might sink into the moon’s soil and bury its occupants alive.

NASA itself, only three years old at the time, had no portable computers that could guide a spaceship. No way of talking to the astronauts as they were on the way. None of the metal alloys engineers would use on the spacecraft were yet invented.

The president and his staff understood what the space program was up against. After making the proposition, Kennedy stated: “No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

It was estimated that the costs for the Apollo program would reach $40 billion—equivalent to $391.6 billion in 2022. Even the International Space Station—the most expensive single item ever constructed—did not cost half this figure over its 20-year lifespan.

But it was not a lunatic idea. By the early 60s, Americans were itching to beat the USSR in some way. The Soviets were the first to launch a satellite into space with Sputnik in 1957 and, in April 1961, put the first human being in space.

Through the next eight years, NASA had to solve thousands of problems to safely get humans to the moon. “Every one of those challenges was tackled and mastered between May 1961 and July 1969,” Smithsonian continued.

Not all went smoothly. The first crewed mission of the Apollo program ended in disaster in 1967 when all three of its crew members died in a fire during a launch rehearsal test. And the Apollo 10 crew—who conducted the “dress rehearsal” months before the Apollo 11 moon landing—were seconds from blacking out and crashing on lunar soil after the spacecraft began spiraling out of control.

Yet the blood, sweat and tears expended by hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers and factory workers fulfilled Kennedy’s prerogative—before the decade was out. In that way, when Neil Armstrong made the small step to put the first human footprint on the lunar surface during the Apollo 11 mission, it truly represented a giant leap for mankind.

It began decades of technological progress and unquestioned U.S. leadership in exploration and military prowess. Young minds were fascinated into the decades that became known as the Space Age—complete with the space movie epic Star Wars and TV series Star Trek.

But what was accomplished in eight years reveals a fundamental drive for mankind to explore—and an incredible reason for it.

The All-time Moment

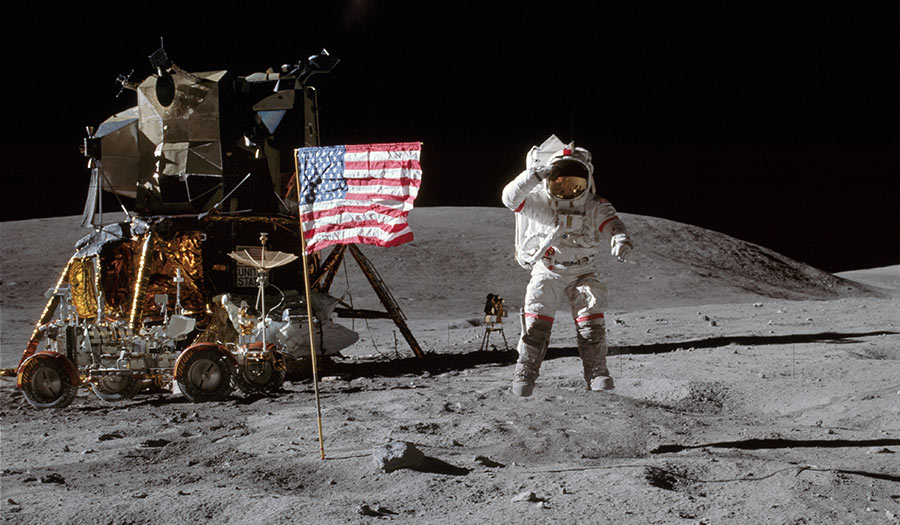

More than 50 years ago was a moment millions of now grown-up Baby Boomers say defined their childhood: when they watched NASA’s Apollo 11 make the first manned lunar landing. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon together. Michael Collins zipping along in orbit in the command module.

But little did viewers back on Earth understand the complexity of the mission. The descent was a near-miss. Armstrong manually flew the Eagle—the name given to the module that would land on the moon—to avoid a rocky area. They found a landing spot with only two seconds of fuel to spare before a mandatory abort.

When the Eagle touched the ground, Armstrong and Aldrin were supposed to sleep for five hours before opening the hatch. But the two—one a hardened X-15 test pilot and the other an Air Force veteran—went ahead with preparations. Armstrong’s heart rate exceeded 160 beats per minute at this time.

Next, Armstrong squeezed through the opening just large enough for his space-suited frame. He pulled a ring that activated the TV camera, and some 600 million people—one-fifth of the world population at the time—began watching the ghostly black-and-white images on live television. It was the public’s first moving-picture view of the moon’s surface. People came to a standstill as they watched, from Marines fighting in the jungles of Vietnam to children at Disneyland.

A plaque on the ladder of the Eagle, which was left permanently on the lunar surface, states: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” It was signed by President Richard Nixon and the three astronauts.

Armstrong described the surface as “very fine-grained” and “almost like a powder.” When he made the epic step, it became, as he said, “one giant leap for mankind.”

Soon after, Aldrin joined his partner and described what he saw as “magnificent desolation.” The lunar pioneers then spent the next 2.5 hours picking up soil samples, taking photos and testing different walking methods on the slippery surface in one-sixth of Earth’s gravity.

From 1969 to 1972, 12 men landed on the moon over six Apollo missions. The last time human footprints graced the lunar surface was during the Apollo 17 mission.

Waning Interest

Public interest in space exploration had steadily declined by the last Apollo mission. At that point, it was clear the U.S. had space superiority. Cold War tensions began easing—evidenced by joint space projects with the Soviets such as the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, which involved the docking of the two superpowers’ spacecraft in 1975. In addition, domestic issues were on the rise in the homeland. With inflation rising, the government was under pressure to reduce spending.

In 1973, 59 percent of those polled by Gallup said they favored cutting funding for space exploration.

“The Apollo project was a political project,” Sergei Khrushchev, the son of late Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, alleged in an interview with Scientific American.

The moon landing made a bold statement, but many other important areas of space exploration exist. And NASA’s programs have indeed flourished since, with the International Space Station, Mars rovers, the Hubble Space Telescope, automated exploration of the outer regions of the solar system such as New Horizons visiting Pluto in July 2015, and most recently the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope—the largest of its kind in space today.

Yet the notion of putting human beings on another planetary body was never truly extinguished.

Going Back

There is a renewed race to get human beings back on the moon, although it has a lower profile than the one in the 60s. NASA is calling the new program Artemis, after the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology.

For the next go-around, the space agency wants its moonwalkers to reflect today’s more diverse astronaut corps, thus the name of Apollo’s sister. Artemis was goddess of the hunt as well as the moon.

After several canceled launches due to fuel leaks and engine issues, NASA is now setting sights on getting its new moon rocket test launched in mid-November.

Once in space, the crew capsule atop the rocket will aim for lunar orbit with three test dummies, a crucial test rehearsal before astronauts climb aboard in 2024. People last walked on the moon in 1972.

The next generation of rockets NASA will use for the Artemis program is designed to reach farther destinations such as Mars.

“We’re on the eve of a historic launch kicking off the Artemis era and this contract shows NASA is making long-term plans toward living and working on the Moon, while also having a forward focus on getting humans to Mars,” Lisa Callahan, vice president and general manager for Commercial Civil Space at Lockheed Martin, said in a statement.

The desire to put man back on Earth’s nearest neighbor may seem like pure nostalgia. But there is a fascinating point to man’s inherent need to explore.

What’s Out There?

Think of all the reasons man is driven to explore outer space.

For one, it pushes us to progress in ways we now mostly take for granted.

In 60 years, we went from being bound to Earth to eventually exploring every planet in the solar system. With satellite coverage, we can talk on cellphones and drive with GPS. Technologies for industry, transportation and medicine, as well as our understanding of human health, have advanced because of space travel. Also, the photographic and video images of places never seen before have aroused imaginations and inspired generations to continue the quest of understanding humanity’s place in the universe.

Ultimately, space exploration missions answer fundamental but profound questions mankind has asked for millennia. Questions NASA listed: “What is the nature of the Universe? Is the destiny of humankind bound to Earth? Are we and our planet unique? Is there life elsewhere in the Universe?”

These same questions have motivated humans to devote their lives to searching the great unknowns: Cortez and Columbus claiming land in the New World, crews racing to be the first to reach the South Pole in Antarctica, Theodore Roosevelt charting the River of Doubt in the Amazon, and the ongoing effort to reach greater depths in the oceans’ trenches.

Man has an insatiable need to find anything and everything that is beyond his line of sight. David Scott, an astronaut who set foot on the moon during the first rover mission in Apollo 15, summarized this: “As I stand out here in the wonders of the unknown at Hadley, I sort of realize there’s a fundamental truth to our nature. Man must explore. And this is exploration at its greatest.”

Eyes to the Sky

There is one source that can explain our passion for understanding the unknown: the Being who created everything.

Note: “Thus says God the Lord, He that created the heavens, and stretched them out” (Isa. 42:5). “I have made the earth, and created man upon it: I, even My hands, have stretched out the heavens, and all their host have I commanded” (45:12). “It is He that sits upon the circle of the earth, and the inhabitants thereof are as grasshoppers; that stretches out the heavens as a curtain, and spreads them out as a tent to dwell in” (40:22).

The heavens glisten with the fingerprints of a Creator. It is no wonder Buzz Aldrin quoted on the last night of his mission before splashdown: “When I consider Your heavens, the work of Your fingers, the moon and the stars, which You have ordained: What is man, that You are mindful of him?” (Psa. 8:3-4).

Mr. Aldrin was quoting a man who lived 3,000 years ago: David—who slayed Goliath and was king of ancient Israel.

Both Mr. Aldrin and King David realized how tiny and insignificant they were. So does anyone who has seen the vastness of the universe.

The same Being who created the stars also made human beings, and designed us to feel this way. Notice: “He has set the world [eternity] in their heart, so that no man can find out the work that God makes from the beginning to the end” (Ecc. 3:11).

God is eternal—He is infinite! But because human beings are finite, “a man cannot find out the work that is done under the sun: because though a man labor to seek it out, yet he shall not find it; yes further; though a wise man think to know it, yet shall he not be able to find it” (8:17).

God put the desire to understand all of His Creation and our place in it into our hearts, so we yearn and search. Space exploration programs are a modern fulfillment of this. But God promised that we would not be able to figure out eternity or fully understand the universe. Therefore, we continue to wonder and explore.

This can sound defeating—until you realize the mind-boggling purpose for every human being who has ever lived.

Again, the answer is contained within God’s Word. Read what comes after the verses Mr. Aldrin quoted from Psalms: “You made [man] to have dominion over the works of Your hands; You have put all things under his feet” (8:6).

What the psalmist explained has enormous implications: God gave man control over everything He made—which is everything!

Your incredible potential exceeds even the grandest accomplishments of mankind. They all pale in comparison to what God has in store for you.

Read The Awesome Potential of Man to grasp the crucial purpose for your life.

More on Related Topics:

- The Future of Energy?

- How Social Media Became a Storefront for Deadly Fake Pills

- Cyberattacks on U.S. Utilities Surged 70 Percent This Year, Says Check Point

- A Robot Begins Removal of Melted Fuel from the Fukushima Nuclear Plant. It Could Take a Century

- Explainer: Why South Korea Is on High Alert over Deepfake Sex Crimes