Reuters/Jorge Cabrera

Reuters/Jorge Cabrera

World News Desk

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowCHICUZ, Guatemala (Reuters) – Matilde Ical Chen was toasting tortillas over a wood fire for the midday meal when the landslide ripped through the Guatemalan Mayan indigenous village of Queja, burying her mother, sisters and grandparents in a torrent of liquid earth and rock.

Ical Chen, 49, grabbed her husband and six small children and ran, barely surviving a fall into a ravine, she told Reuters in Chicuz, a hamlet three hours on foot from Queja, where she and hundreds of other survivors are now sheltered in a primary school after Thursday’s disaster.

“My mother was buried, along with my sisters, their husbands, the whole family, even the grandparents,” Ical Chen said though an interpreter, counting approximately 30 family members who did not escape the mud that rescuers say is up to 50 feet deep.

“We have food here, but I can’t eat for the worry,” she said, clutching a scarf as tears ran down her cheeks.

A deluge linked to storm Eta killed dozens and caused devastation from Panama to Mexico last week. But perhaps nowhere was harder hit than Guatemala, where poor Mayan villages precariously perched on lush mountainsides are susceptible to landslides.

Rescuers say they may never know how many people were buried in the mud in Queja, about 125 miles from Guatemala City. The government has estimated up to 150 lives lost.

But braving loose ground and new landslides that made rescue work perilous, survivors returned on Sunday desperately looking for relatives and scant belongings—clothes, a little food, their livestock.

With the first break from days of relentless rain allowing more access, helicopters buzzed in and out of the village and surrounding hamlets, bringing supplies and rescue workers who recovered at least six bodies, even as new landslides endangered more lives.

At least two people were killed when a light aircraft carrying humanitarian aid for the disaster area crashed in Guatemala City, while another helicopter was forced to make an emergency landing.

Rolando Cal was among the survivors who made the treacherous trek back to Queja, a Poqomchi’ Mayan settlement of about 1,300 people, searching for any of his 23 relatives lost in the mud when the mountainside collapsed after days of rain.

“This is where my whole family and my home were destroyed,” Mr. Cal said, pointing to a pile of rubble where his house once stood, a vast gash of bare earth stark against the lush landscape and remaining houses beyond.

“I no longer have a place to live,” said Mr. Cal, who walked into Queja on Sunday from neighboring Santa Elena, where he has found shelter. “Without food, without money. I’m miserable.”

When a helicopter carrying supplies organized by a retired general, Francisco Mus, arrived in Chicuz, survivors huddled in the schoolyard ran out, desperate for possible news of loved ones left behind. Among some 450 people sheltered at the school, many were saved by Chicuz residents who risked their own lives to clamber into gullies and pull stranded families up with ropes, village official Raul Gualin said.

Bedraggled, and with only the clothes on her back, Ical Chen said she was grateful to the village for taking her in. She too thinks she, her husband and children will not return to Queja now, or maybe ever.

“We will try to find refuge in another place, and not go back there,” she said. “I lost my whole family.”

- World News Desk

- GEOPOLITICS

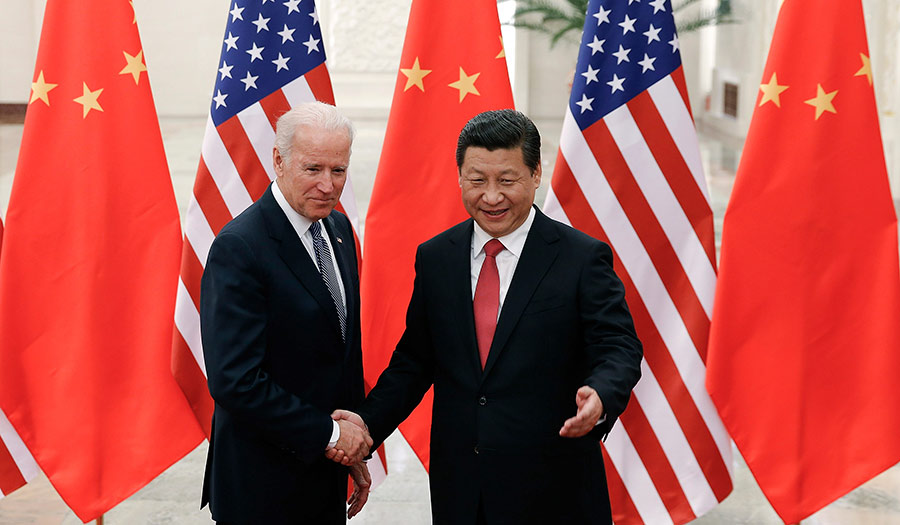

A Worried Asia Wonders: What Will Joe Biden Do?

A Worried Asia Wonders: What Will Joe Biden Do?

Other Related Items:

- Ivory Coast Opposition Leader Calls on Military to Disobey President

- Fighting Over Nagorno-Karabakh Drags Past 6th Week. What’s Behind the Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict?