Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Article

Part 4 of our series covering the implications of Earth’s population growth looks at the distribution of wealth and resources.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

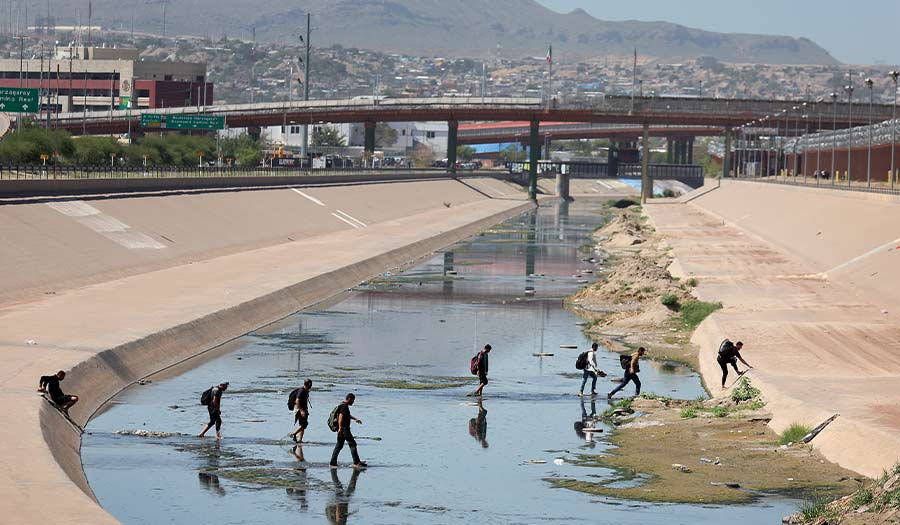

Migrants cross from the Mexican side of the Rio Grande to turn themselves in to U.S. Border Patrol in El Paso, Texas (Sept. 21, 2022).

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Migrants cross from the Mexican side of the Rio Grande to turn themselves in to U.S. Border Patrol in El Paso, Texas (Sept. 21, 2022).

Ted Aljibe/AFP via Getty Images

A group of homeless people rest near their pushcart outside an abandoned building in Quezon City,Philippines (Nov. 29, 2022).

Ted Aljibe/AFP via Getty Images

A group of homeless people rest near their pushcart outside an abandoned building in Quezon City,Philippines (Nov. 29, 2022).

Carl de Souza/AFP via Getty Images

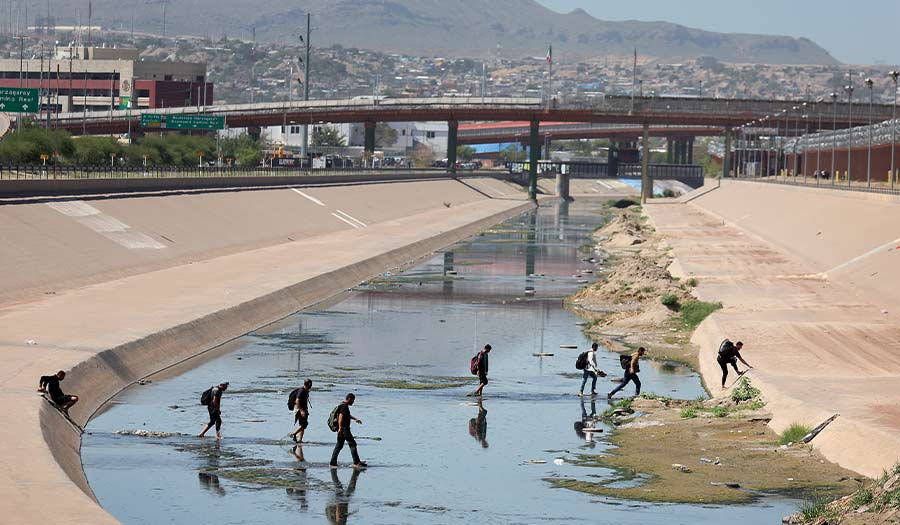

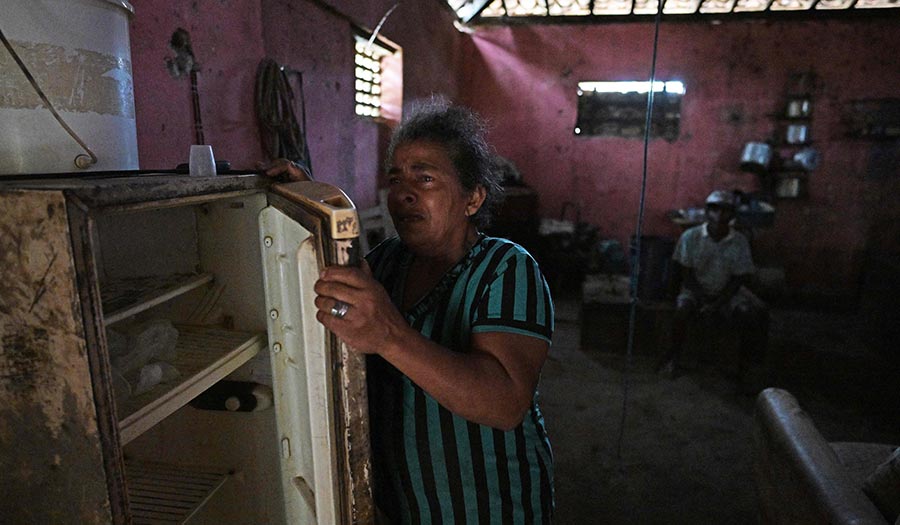

A woman cries while showing her empty fridge at the abandoned house she lives in with her family of eight in Ibimirim, Pernambuco state, Brazil (Aug. 31, 2022).

Carl de Souza/AFP via Getty Images

A woman cries while showing her empty fridge at the abandoned house she lives in with her family of eight in Ibimirim, Pernambuco state, Brazil (Aug. 31, 2022).

Nelson Almeida/AFP via Getty Images

Young people play football at Tekoha Marangatu Guarani indigenous village in the municipality of Guaira, Parana state, Brazil (Oct. 13, 2022).

Nelson Almeida/AFP via Getty Images

Young people play football at Tekoha Marangatu Guarani indigenous village in the municipality of Guaira, Parana state, Brazil (Oct. 13, 2022).

“Global progress in reducing extreme poverty has virtually come to a halt,” the World Bank wrote in the introduction to their “Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022” report.

Nearly 1 in 10 of Earth’s population live in poverty.

The report continued: “After COVID-19 dealt the biggest setback to global poverty in decades, rising food and energy prices—fueled by climate shocks and conflict among the world’s biggest food producers—have hindered a swift recovery.”

Developing nations are hit hardest by this complex and multifaceted problem. Poverty is inexorably linked to inequality. The World Bank added that “by 2030, nearly 7 percent of the world’s population—nearly 600 million people—will still struggle in extreme poverty. Within-country inequality increased in as many countries as it declined, but after decades of convergence, global inequality increased. The poorest have also suffered disproportionate losses in health and education with devastating consequences.”

The World Inequality Lab reported that the “poorest half of the world population owns just 2% of total net wealth, whereas the richest half owns 98% of all the wealth on earth.”

Compounding the issue, the explosion of population growth has seen much of its increase in poor and impoverished areas of the planet.

In the report “A World of 8 Billion” the UN wrote: “Because countries with high levels of fertility tend to be those with relatively low incomes per capita, over time the growth of the world’s population has become increasingly concentrated among the world’s poorest countries, most of which are in sub-Saharan Africa. As the global population grew from 7 to 8 billion, around 70 percent of the added population was in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. When the next billion is added between 2022 and 2037, these two groups of countries are expected to account for more than 90 percent of global growth.”

Take Nigeria. Over the next three decades, the West African nation’s population is expected to soar from 216 million this year to 375 million, the UN said. That will make Nigeria the fourth-most populous country in the world after India, China and the United States.

“We are already overstretching what we have—the housing, roads, the hospitals, schools. Everything is overstretched,” said Gyang Dalyop, an urban planning and development consultant in the country.

Nigeria is among eight countries the UN said will account for more than half the world’s population growth between now and 2050—along with fellow African nations Congo, Ethiopia and Tanzania.

Agriculture makes up nearly 20 percent of Africa’s GDP and more than half of Africans work in the sector, according to the World Bank. Most of this is low-productivity subsistence farming, and the region is a net importer of staples including wheat, palm oil and rice, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization said.

Productivity and crop yields have increased, but they are still the lowest in the world and the FAO says they come nowhere close to keeping up with the continent’s growing population. Without action, the World Bank says Africa’s food import bill, which stood at $43 billion in 2019, could rise to $110 billion in 2025.

“We have to wake up,” Akinwumi Adesina, president of the African Development Bank, told Reuters. “For me, the bare minimum is that Africa is able to feed itself.”

Double-digit inflation, known as a “tax on the poor” because it hits those with low incomes the hardest, has exacerbated inequalities worldwide. While consumers in wealthier countries can rely on savings built up during pandemic lockdowns, others struggle to make ends meet and a growing number rely on food banks.

The World Food Program estimates an extra 70 million people worldwide have been driven closer to starvation since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in what it calls a “tsunami of hunger.”

The Russia-Ukraine war, drought or too much rain, and high energy costs look set to curb global farm production again next year, tightening supplies, even as high prices encourage farmers to boost planting. Countries that are not as directly impacted will also feel the pain as imports and exports are affected.

Crops producing edible oils are suffering from adverse weather in Latin America and Southeast Asia. Production of staples, such as rice and wheat, is unlikely to replenish depleted inventories, at least in the first half of 2023.

“The world needs record crops to satisfy demand. In 2023, we absolutely need to do better than this year,” said Ole Houe, director of advisory services at agriculture brokerage IKON Commodities in Sydney. “[At] this stage, it looks highly unlikely, if we look at the global production prospects for cereals and oilseeds.”

With food prices climbing to record peaks this year, millions of people are suffering across the world, with poorer nations already facing hunger and malnutrition.

“The consequences of food shortages are grim,” The Economist wrote. “Going hungry raises the risk of chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes. Malnutrition does not just mean people eat too little and get thin. Particularly in cities, those who cannot afford nutritious meals buy cheap, packaged foods instead, and the poor are increasingly in danger of obesity.”

Food import costs were, as of this writing, already on course to hit a near $2 trillion record in 2022, forcing poor countries to cut consumption.

Global wheat availability will be down for the first half of 2023. Flooding in Australia, the world’s second-largest wheat exporter, caused extensive damage to the 2022 crop and a severe drought is expected to shrink Argentina’s wheat crop by almost 40 percent.

A lack of rainfall in the U.S. Plains, where the winter crop ratings are running at the lowest since 2012, could dent supplies for the second half of 2023. For rice, prices are expected to remain high as long as export duties imposed by India, the world’s biggest supplier, remain in place.

Economic hardship has also been growing in Western nations. A recent survey conducted by Pew Research Center found that “one-in-four U.S. parents say there have been times in the past year when they could not afford food their family needed or to pay their rent or mortgage. A similar share (24%) say they have struggled to pay for health care their family needed, and 20% of those who needed child care say they haven’t always had enough money to pay for it.”

The series concludes in Part 5: Government Solution?

This article contains information from Reuters and The Associated Press.

- Real Truth Magazine Articles

- POLITICS

Government Solution?

Government Solution?