Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images

Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images

Article

The Bible was promised to remain pure and preserved over thousands of years. Records show this promise has not been broken.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe Now“Bring the scroll and read it to me,” King Jehoiakim commanded. His princes had just told him of a mysterious document written by one of God’s prophets. It was told to contain a disturbing prophecy concerning their fate.

A subordinate was sent to fetch after the scroll, unroll it and begin reading to the king of Judah as he warmed himself in front of a fireplace.

To the astonishment of the princes who stood by, each time the man finished reading a part of the text, the king inexplicably grabbed the scroll and cut out the section with a knife before tossing it into the flames!

Instead of pitching the entire scroll into the fire at once, the irreverent king repeated this bizarre ritual until the entire sacred manuscript was burnt up. The princes begged the king to not desecrate God’s Word, but he snubbed them and threw each piece in until the whole scroll was ashes. In the king’s twisted mind, the words and the events they described were gone forever.

Undeterred, God ordered the scroll’s writer—the prophet Jeremiah and his assistant—to rewrite the text. He then punished the king for his brazen disrespect of His message. God banished the monarch’s descendants from the throne and declared that his corpse would be left to decompose like a dead animal on the streets of Jerusalem (Jer. 36:20-30).

Allow this Old Testament Bible account to illustrate the lengths God went to preserve Scripture. He would not allow even a small section of His written words to be destroyed and severely punished those who desecrated them.

For us today, burning a Bible would not mean God’s words are gone forever. The scriptures are one of the most published texts of all time. Yet many today do share Jehoiakim’s disregard for what God has to say. It is fashionable to view His words as cobbled together musings of uneducated shepherds and religious fanatics.

But not everyone is so openly hostile toward Scripture. They are open to the idea of the Bible being God’s Word, but they struggle to know if the book on their shelves represents the original Hebrew and Greek text as inspired and given by God. Does canonized Scripture match the original words and their true intent?

The Bible says every word of God is pure (Prov. 30:5). The psalmist added, “The words of the Lord are pure words…purified seven times” (Psa. 12:6). Would God put all this effort into ensuring the integrity of His words only to let them corrupt over time? He promised they would not.

If fallible human beings can successfully preserve the authenticity of crucial documents, such as government constitutions or financial reports, God can preserve His Book.

The story of how He divinely engineered events to maintain the accuracy of the Bible over thousands of years proves He did keep His Word.

“My Words Shall Not Pass Away”

Jesus Christ said in Matthew 24:35: “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but My words shall not pass away.” He even more precisely stated, “Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled” (Matt. 5:18).

Jesus Christ is called the Word of God (John 1:1, 14). He would surely understand all there is to know about the scriptures. Therefore, to learn more about the canon of Scripture we should focus on what Christ said about the Bible.

In Luke 24:44, Jesus explained that there are three major divisions of the Old Testament: The Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms. He then called them “scripture” in verse 45. The Old Testament would have been the only Bible Christ had as He walked the Earth. The New Testament would be written and then officially compiled decades after His death.

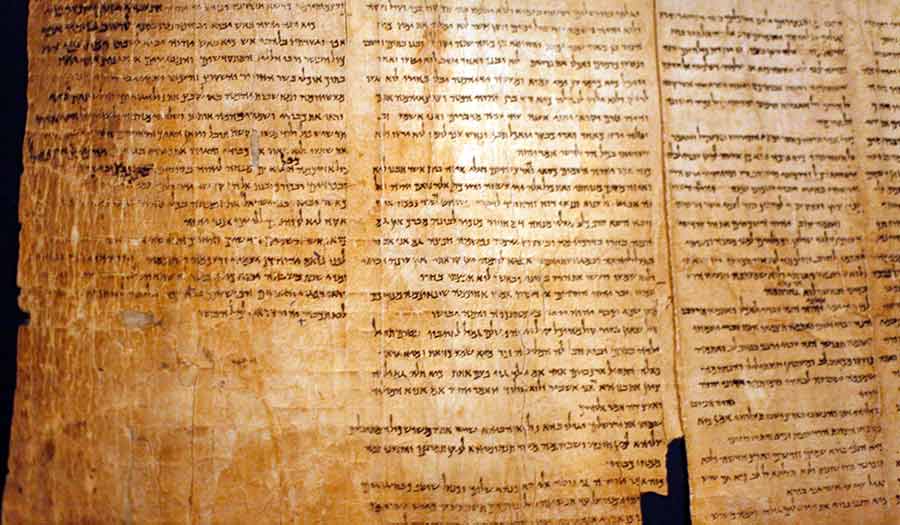

You may have wondered why archeologists and religionists were so excited about the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls nearly 75 years ago and subsequent Bible-related discoveries in the same area. It is directly connected to what Christ said about the Old Testament.

In 1947, a Bedouin shepherd discovered a leather scroll in a cave in Wadi Qumran near the Dead Sea. The 2,000-year-old document was a copy of the Old Testament book of Isaiah. Archeologists found that the scroll’s text fundamentally agreed with the current book of Isaiah, including its 66 chapter divisions.

Within four years of this find, more manuscripts containing 19 books of the Bible were unearthed in nearby caves. These documents, all dating 100-300 years before Christ walked the Earth, helped prove that the Old Testament held its authenticity over the centuries.

Those who follow this subject closely know that there is some variation between the text discovered near the Dead Sea and official Bible manuscripts. Yet this was expected since Jesus never recognized the Dead Sea sects as having authority over maintaining the Masoretic Hebrew text (more on this later).

Bible translations, even based on official text, will always have certain variations. Unless you are reading the Old Testament in its original Hebrew or the New Testament in its original Aramaic or Greek, you are likely reading either a word-for-word or a thought-for-thought translation. Do these inevitable variations mean the Bible cannot be trusted? Far from it.

Language translators know there are always gaps in translation when converting one language to another. Certain words or phrases can be unique with no corresponding rendition in the new language. Also, translators can inadvertently or advertently interject their own interpretation into the text.

God knew this would happen when He chose to use human beings to preserve Scripture. He intended His words to remain understandable to future generations. The Bible is a living book using living languages that change over time. The fact that God’s Word remains understandable to a contemporary audience proves He is guiding the process.

There are two types of translations you can consider for your Bible study—word-for-word and thought-for-thought.

Word-for-word Bible translations attempt to convert each word to the new language. They are more trustworthy than thought-for-thought translations. However, one of the limitations of word-for-word translations is the original meaning can get lost when brought into a modern language. This is why some Bible verses are difficult to fully understand or appear to contradict other verses.

A thought-for-thought translation is an attempt to convey the intended meaning of a passage. These are good supplements to a word-for-word translation—but there are many, many versions of these and most do not have the ability to know which is best.

Perhaps the most reliable English translation is the King James Version from the year 1611. It is a word-for-word translation that effectively conveys the authors’ intent.

The Role of the Jews

The Bible says in several places that God selected the Jews to preserve Scripture. Notice: “What advantage then has the Jew? Or what profit is there of circumcision? Much every way: chiefly, because that unto them were committed the oracles of God” (Rom. 3:1-2). Oracles here refers to God’s words.

History reveals that none of the Hebrew Bible was lost. Even through war and persecution, the Jewish people preserved the books of the Old Testament in Jesus’ day so that they are the same as ones read in synagogues and churches today.

What the Jews preserved is known as the Masoretic Hebrew text. The Masoretic text was meticulously assembled and codified from the original text of Hebrew Scripture.

When the final codification of each section was complete, the Masoretic scribes counted and recorded the total number of verses, words and letters in the text to allow any revisions to be detected. This rigorous treatment of the Masoretic text explains the remarkable consistency found in Old Testament texts since that time. The Masoretic text is universally accepted as the authentic Hebrew Bible, The Encyclopedia Britannica states.

What more did Christ say about Scripture? He said it was preserved “beginning at Moses and all the prophets” (Luke 24:27). Most do not consider that mankind had the means to preserve text even thousands of years ago—they were not entrusted to ignorant or uneducated men.

Speaking of Moses, the book of Acts says: “This is he, that was in the church in the wilderness with the angel which spoke to him in the mount Sinai, and with our fathers, who received the lively oracles to give unto us” (7:38). Moses recorded and compiled all five books of the Law (also called the Pentateuch) during Israel’s 40 years in the wilderness. He used pre-Flood documents and other sources to write Genesis.

Moses presented the five books to the priesthood of Israel who stored them in the Ark of the Covenant, a special chest designed to preserve these writings among other items (Deut. 31:9). Under the authority of the high priest, scribes made copies of these scrolls for distribution. Others besides Moses also contributed important parts of the Law, including Samuel the priest (I Sam. 10:25).

But it was Ezra who may have been the most prominent figure in the preservation of the Hebrew scriptures. Few, even among Bible readers and Christian teachers, fully appreciate his role in the preservation of God’s Word.

Ezra was a priest and scribe in the 5th century BC who gathered all the books and made the final canonization of the Old Testament. Along with meticulously copying the scriptures as he received them, Ezra was guided by God to insert editorial notes to bring clarity to readers of his time and in the future. Some of the notes attributed to Ezra are Genesis 14:7, 17; 23:2, 19; 36:31-39. The priest later added comments in Deuteronomy 34:5-6, 10 about Moses’ death since he obviously could not record his own burial.

Through Ezra and others, God ensured safekeeping of the scriptures during the Jews’ captivity in Babylon. The prophet Daniel’s position of authority in the gentile nation allowed him to preserve several copies (Dan. 9:2, 11).

Divine protection of the Bible also came after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in AD 70. Preservation of the text subsequently became the job of religious sects instead of the Jewish state.

Some Jews did try to introduce illegitimate copies of the scriptures over the centuries. For instance, the Septuagint—a Greek translation of the Old Testament—was translated by 72 Jewish scholars. It disagrees with the official Hebrew version.

Yet there were Jews who ensured the integrity of the original text as God promised. Christ promised in Matthew 26:54, 56: “But how then shall the scriptures be fulfilled, that thus it must be?…But all this was done, that the scriptures of the prophets might be fulfilled.” Jesus would not have confirmed the authenticity of Scripture had the Jews not kept it properly.

Then Came the Greeks

Even though the first-century Jews especially of higher authority rejected Jesus Christ, they could not prevent God from preserving all of Scripture.

A prophecy in Isaiah 8:13-17 explains that the Messiah would have servants bind up and seal the written record of His life. In order to fulfill that prophecy, the writings about Christ—which would form the New Testament—would have to be given as much importance as the preserved words of the Old Testament.

To circumvent Jews who would not accept New Testament writings, God turned to the Greek language. Greek writers and speakers picked up the responsibility of preserving the gospels of Christ and the writings of the New Testament Church. Eventually, the writings from the apostles and other disciples of Christ went on to be canonized as part of the Bible.

The apostle Paul assured those in Rome that the Jews’ unbelief had no bearing on the integrity of the Bible. Notice: “What if some [Jews] did not believe? Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect? God forbid: yes, let God be true, but every man a liar; as it is written, That you might be justified in your sayings, and might overcome when you are judged” (Rom. 3:3-4).

The Jews originally had an advantage over the Greeks since they first received God’s oracles. When the Jews spurned Christ’s message, God raised the apostle Paul to go to the Greek-speaking world with the same message.

Paul went almost exclusively to the Greeks and the Greek-speaking world fulfilling an Old Testament prophecy repeated in Romans 10:19-20: “But I say, Did not Israel know? First Moses said, I will provoke you to jealousy by them that are no people, and by a foolish nation I will anger you. But Isaiah is very bold, and said, I was found of them that sought me not; I was made manifest unto them that asked not after Me.”

God used the “foolish” Greeks (called this based on their vanity and ignorance of the Old Testament scriptures) to provoke the Jews to jealousy, even though the Greeks did not seek God on their own. From this point forward, God made “no difference between the Jew and Greek” (Rom. 10:12).

This transition to working with the Greeks instead of exclusively working with the Jews proves God always intended to spread His Word to all mankind regardless of ethnic background.

God inspired the Greeks to copy and publish the New Testament text in their language. The Samaritans, Latins and Egyptians all made attempts to translate the New Testament, but they altered and thus corrupted the text. Only the Greeks accurately copied and preserved the New Testament.

Nearly 4,500 Greek manuscripts examined by experts confirm the integrity and purity of the modern New Testament. In 1935, a fragment of John’s gospel in Greek dating from the time of Roman Emperor Trajan, AD 98 to 117, was discovered in Egypt. The fragment indicated that the entire New Testament, in proper order, was circulating within 20 years of the apostle John’s death.

This is evidence God’s Word was secured across thousands of years and through multiple language translations. But how did Scripture successfully make it across countries and continents?

The New Testament record was complete after John, but much of the original texts remained local. In 1453, the Turks conquered Constantinople, the capital of the Greek world. As the Greeks fled west, they took their preserved Bible manuscripts. These manuscripts permeated a religious world dominated at the time by the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible.

The Latin Vulgate was the work of Jerome, a biblical scholar commissioned by the Catholic Church to produce a Latin version of the Bible. He used many Latin translations which all differed. As a result, the Vulgate is not closely based on the original Greek New Testament. It instead traces back to the Septuagint and Alexandrian influences. Jerome himself admitted the Latin translations he used were corrupted.

One example of its flaws is the addition of text in I John 5:7, which alludes to God as a trinity—Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This made it into the King James Version via the Latin Vulgate. However, this verse was in none of the Greek manuscripts.

Despite its inaccuracies, the Latin Vulgate dominated the Western world for 1,300 years. It was the only “Bible” accessible during the Middle Ages.

The addition in the epistle of John notwithstanding, the KJV Bible came from authoritative Greek manuscripts for the New Testament and the Masoretic Hebrew text for the Old Testament.

Other Books?

Where do the apocrypha and the so-called lost books of the Bible fit? To begin, neither were intended to be a final part of Bible canon.

The apocrypha contains seven whole books and portions of three others. They are usually found in today’s so-called Catholic Bible. The seven full apocryphal books are: Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch and I and II Maccabees. The partial books are “Song of the Three Holy Children” inserted in the middle of Daniel 3 along with “Susana and the Elders” and “Bel and the Dragon” added at the end of Daniel.

Apocrypha is a Greek word that means “hidden” or “secret.” This likely adds to their appeal—people are intrigued by secrets and hidden knowledge. But the apocrypha contains a mix of historic truth and error. In English, synonyms for “apocryphal” include the words “inauthentic” and “ungenuine.” This shows even society vaguely understands these writings cannot be trusted!

But if you still think the apocrypha could be of some use, consider this.

The New Testament contains approximately 263 direct and 370 indirect quotations of the Old Testament. In each of these, Christ and the apostles never referenced the apocrypha. Not a single time.

The Jewish scribes authorized to preserve the Old Testament never accepted the apocrypha. Jerome left it out of the Vulgate because he knew it was filled with error. Even the Catholic Church held off declaring the apocrypha equal with official books of the Bible until the Council of Trent in 1563.

Another popular apocryphal piece is the book of Enoch, which is filled with eschatological theories and supposed revelations. Proponents of the book tie its validity to a single reference to the Bible patriarch Enoch in Jude 1:14-15. Yet the verse makes no mention of a book, and the book goes far beyond the one sentence in the short book of Jude.

The so-called “lost books of the Bible” could be a little trickier to discern as Bible canon since they are actually referenced in authorized Scripture. The books and their location in the Bible are:

• Book of the Wars of the Lord (Num. 21:14)

• Book of Jasher (Josh. 10:13; II Sam. 1:18)

• Book of the Acts of Solomon (I Kgs. 11:41)

• Book of Nathan the Prophet (I Chron. 29:29)

• Book of Gad the Seer (I Chron. 29:29)

• Prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite (II Chron. 9:29)

• Visions of Iddo the Seer (II Chron. 9:29)

The last four books were listed in books that Ezra canonized. But he did not add them to the canon because God never authorized him to do so. In the sense, these “lost books” were not lost. They simply were not intended to be canonized.

Yet these books were listed in Scripture. Why? Perhaps they were drafts God inspired to help contribute to larger books in the Bible. Whatever the reason, God did not include them in the final version of His Word.

Bible canon is a vast and technical subject with enormous implications for those of the Christian faith. Ultimately, Bible readers need to trust that the words they study and live by are pure and unadulterated.

You can trust the veracity of the modern Bible as God’s inspired Word, and that it carries the same message as it did millennia ago. Consider the alternative: to trust and worship a God unable to ensure the only words He left were preserved and remained pure. Such a Being would not be worthy of worship.

To learn even more about the authenticity of the Bible, read our two-part Real Truth article “How Was the Bible Canonized?” on our website.