- World News Desk

- INTERNATIONAL

| “I’m very worried,” a 64-year-old bookseller said. “Before, things were always difficult. But there was always one bus. One way to get home. Now, there are none.” |

- World News Desk

- MIDDLE EAST

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) – Iran marked the 47th anniversary of its 1979 Islamic Revolution on Wednesday as the country’s theocracy remains under pressure, both from U.S. President Donald Trump who suggested sending another aircraft carrier group to the Middle East and a public angrily denouncing Tehran’s bloody crackdown on nationwide protests.

- Articles

- HOLIDAYS

Misting cologne into the air, a husband grins in the mirror with satisfaction. Everything has been set: a bundle of roses adorns the dining room table, tea light candles glimmer in the entryway, and tucked inside his pocket is an ivory gift box with a diamond bracelet for his wife. He straightens his tie, confident it will be the perfect Valentine’s Day.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe Now- World News Desk

- MIDDLE EAST

JERUSALEM (AP) – As the bodies of two dozen Palestinians killed in Israeli strikes arrived at hospitals in Gaza on Wednesday, the director of one asked a question that has echoed across the war-ravaged territory for months.

- Articles

- RELIGION

| What has Jesus been doing for the past 2,000 years up to our time? Here’s what the Bible says. |

- World News Desk

- PROFILE

| The landslide victory was due, in large part, to the extraordinary popularity of Japan’s first female prime minister, and allows her to pursue a conservative shift in Japan’s security, immigration and other policies. |

From the Editor

- Personals from the Editor

- RELIGION

| The idea of an ever-burning hell has frightened countless millions. Does it really exist? |

- Articles

- AFRICA

| The attack is the latest in a surge in violence in the state of Kwara, as well as other conflict hot spots, as armed groups in Nigeria challenge the state’s authority and compete with one another. |

- Articles

- HOLIDAYS

| Valentine’s Day is the world’s “holiday of love.” Since the Bible states that God is love, does He approve of the celebration of this day? The answer may surprise you… |

- World News Desk

- INTERNATIONAL

| Scientists set their Doomsday Clock closer than ever to midnight, citing aggressive behavior by nuclear powers, fraying nuclear arms control, conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East and AI worries among factors driving risks for global disaster. |

- Articles

- INTERNATIONAL

| The deployment of a powerful model of Turkish combat drone to a remote airstrip on Egypt’s southwestern border signals a sharp escalation in Sudan’s civil war. |

- Articles

- GEOPOLITICS

| The last remaining nuclear arms pact between Russia and the United States is set to expire Thursday, removing any caps on the two largest atomic arsenals for the first time in more than a half-century. |

- World News Desk

- ANALYSIS

| Here is how the system operates and who the main figures are in today’s Iran. |

- Articles

- AFRICA

| Paramilitary fighters kidnapped children during their takeover of the Sudanese city of al-Fashir in October and in other attacks in the Darfur region over the course of Sudan’s civil war, in some cases killing their parents first, witnesses say. |

- World News Desk

- GEOPOLITICS

| While some traditional allies of the U.S. have responded cautiously, and in a few cases have rejected Mr. Trump’s offer, others including nations that have long had strained ties with Washington have accepted. |

- World News Desk

- ASIA

| The Syrian government and Kurdish forces declared a ceasefire deal on Friday that sets out a phased integration of Kurdish fighters into the state, averting a potentially bloody battle and drawing U.S. praise. |

- Articles

- SOCIETY & LIFESTYLES

| God has a plan for everyone battling depression and despair. |

- Articles

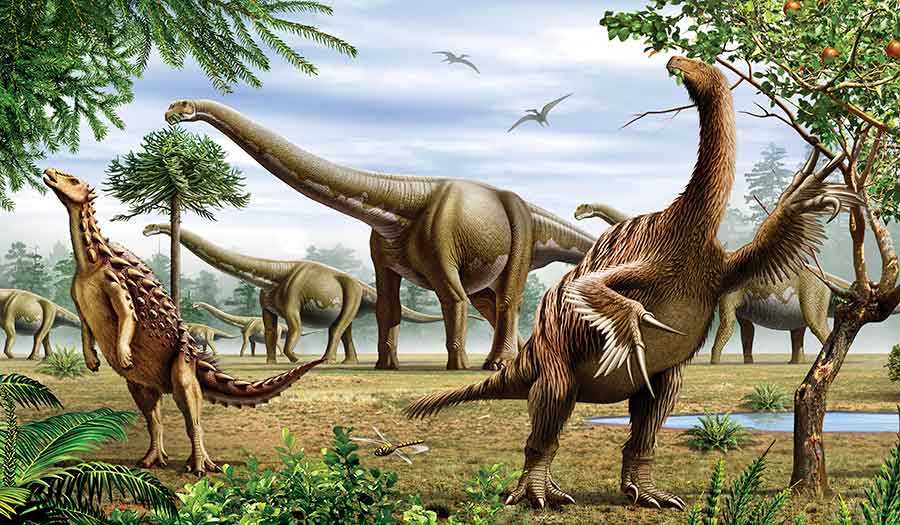

- SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

| The Bible says a lot more about prehistoric creatures than most realize. Here’s how what it says aligns with the geological record. |