Jim Bourg/AFP/Getty Images

Jim Bourg/AFP/Getty Images

Article

In developments unthinkable a few years ago, the two powers continue to negotiate the nuclear issue and appear willing to work together to resolve the crisis in Iraq.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowIran’s true intentions have long been a tiny, fast-moving target for the United States. Washington has rarely hit the mark. Complicating matters are the seemingly wild swings in Tehran’s approaches to foreign policy.

Take the nation’s last two presidents, for instance. From 2005-2013, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad held the reins of the Iranian nation and effectively alienated it from the U.S. and the rest of the world. Mr. Ahmadinejad did not let his disdain for the West go unnoticed and was quick to criticize America at every turn.

His tenure brimmed with inflammatory rhetoric. During a United Nations conference held in New York in 2010, he blasted the U.S. with a continuous stream of hate-filled speech. CNN reported at the time: “Though incendiary statements from Ahmadinejad are nothing new, tension in the hall grew as the Iranian leader recounted various conspiracy theories about the September 11 attacks.

“‘Some segments within the U.S. government orchestrated the attack,’ Ahmadinejad told the General Assembly.

“He followed with the claim that the attacks were aimed at reversing ‘the declining American economy and its scripts on the Middle East in order to save the Zionist regime. The majority of the American people, as well as most nations and politicians around the world, agree with this view.’”

During Mr. Ahmadinejad’s time in office, he constantly flaunted Iran’s nuclear ambitions. This move brought strong international sanctions that severely affected quality of life for the nation—and plummeted relations between it and the U.S.

In June 2013, Iran was ready for a change and voiced that opinion in the presidential election. Citizens voted in Hassan Rouhani, who campaigned with a pledge of “reconciliation and peace.”

Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty Images

Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty ImagesHis inaugural speech demonstrated his drastically different approach. The Guardian reported: “‘People want change,’ said the new president, who described himself as the representative of all Iranian people and not only those who voted for him in the election. ‘People want to live better, to have dignity as well as a stable life. They also want to recapture their deserving position among nations,’ he said.”

Mr. Rouhani has stood in stark contrast with his predecessor at every turn. Soon after his election in June 2013, CNN described him as having “all-round credentials in Iran’s institutions that include senior cleric, former commander of Iranian air defenses and [as] an intellectual with three law degrees, including from a university in Scotland. He has a reputation for shunning extreme positions and bridging differences.”

The new president took no time to positively engage the U.S. Within a few months, he shared a 15-minute phone call with U.S. President Barack Obama—the first direct conversation between the top leaders of the two nations since the 1979 Islamic revolution.

The historic call came after a visit by Mr. Rouhani to New York for a United Nations General Assembly in which he called America a “great nation,” The Guardian stated.

Choosing the words “great nation” further separated Mr. Rouhani from Mr. Ahmadinejad who regularly referred to the U.S. as the “great Satan.”

In December 2013, Mr. Rouhani signed an agreement with the West to negotiate a plan for Iran’s nuclear program. “The agreement, which was finalized in Geneva and will endure for six months while international negotiators seek a more comprehensive, long-term settlement, provides Iran modest relief from the sanctions that have dealt a heavy blow to its economy in exchange for a series of steps to prevent the Iranians from weaponizing nuclear technology,” CBS News reported. On July 20, both sides agreed to extend the deadline another four months.

Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty Images

Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty ImagesMr. Rouhani’s positive approach has continued since the agreement. At an annual Iranian parade in April 2014, Reuters quoted the president as saying: “We told the world during the (nuclear) talks and we repeat that we don’t support any aggression…We support dialogue.”

A few years ago, such dialogue would have been unthinkable. Equally unexpected is that events in the Middle East are pushing Iran and the U.S. to pursue common goals. Can the two nations really work together—as unlikely partners—or is America reading the situation all wrong?

Common Ground?

In January 2014, Iran and the United States gained a surprising mutual interest with the emergence of terrorist organization Islamic State (previously known as ISIS), which has taken over parts of Iraq. The group is a split-off jihadist group that formed from members of al-Qaida and has brashly claimed the beginning of a new caliphate (an Islamic state) in Iraq under the leadership of self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The Council on Foreign Relations wrote: “ISIS now controls a volume of resources and territory unmatched in the history of extremist organizations. It possesses the means to threaten its neighbors on multiple fronts, demonstrating a military effectiveness much greater than many observers expected. Should ISIS continue this pattern of consolidation and expansion, this terrorist ‘army’ will eventually be able to exert a destabilizing influence far beyond the immediate area.”

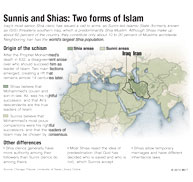

Notably, the Islamic State is a radical sect of Sunni Islam, while Iran and the ruling party in Iraq are rival Shia.

Iran does not want to see its Shia neighbor fall into the hands of Sunni radicals. The United States does not want to see Iraq fall into the hands of extremists. Because of this, the situation provides a common interest for Tehran and Washington. Again, this was all completely unimaginable a few years ago.

Misreading the Middle East

Yet Middle East politics have always been an enigma for the United States. A central reason for this confusion is time. This is definitely the case with seeking to understand Iranians (who historically have been known as Persians). For instance, American citizens live in a nation that turned 238 this year. Persians, on the other hand, have thousands of years of attachments to their homeland. Put another way, America turned 200 in 1976. By contrast, in 1972, Iran celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of Cyrus the Great starting the Achaemenid Empire.

STR/AFP/Getty Images

STR/AFP/Getty Images For the region as a whole, though, a top confusing feature is the Shia-Sunni divide in Islam. To Western eyes, the differences between the two sects of this religion seem superficial. After all, they share the same prayers, view the Koran as holy, and lead similar lives.

Yet, while Sunnis and Shias have many of the same beliefs, they have had nearly 1,400 years to build separate cultural and religious identities. In other words, this divide runs deep. For many, this sectarianism defines them—it is their identity.

It all started after the death of the founder of Islam, Mohammed, in AD 632. A dispute arose among his followers about who would succeed him as leader of the religion. Those who would come to be known as Sunnis thought that anyone could be elected to top positions as long as they were devout and qualified Muslims. The soon-to-be Shia felt that only those of Mohammed’s bloodline should be in charge.

There are other differences in beliefs, but the main point is that the disagreement has been ongoing for almost 1,400 years. It is not something that can be solved with a mutual apology and a firm handshake.

The Shia-Sunni divide drives the bitter rivalry between Iran (Shia) and Saudi Arabia (Sunni); the ongoing clashes between the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad (an offshoot of Shia) and rebel forces (Sunni); and again the growing civil war between Iraq’s government (majority Shia) and the militant group Islamic State (radical Sunni).

Throughout the centuries, there have been historical clashes between these two groups, yet much of the time they have lived relatively peaceably.

So what is different today? The two sects tend to come to blows when there are power vacuums. And since the start of the Arab Spring in 2010, there have been plenty.

Iran also stokes Shia-Sunni tensions. Since the seventh century, when Muslims waged a successful conquest in the region, the majority of the Iranians (then known as Persians) have adhered to the Koran. With the rise of the ayatollahs after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the nation has been majority Shia—with a main goal to export their revolution to other nations.

The Council on Foreign Relations explained part of the motivation for Iran’s actions: “Shia identity is rooted in victimhood over the killing of Husayn, the Prophet Mohammed’s grandson [whom the Shia felt should rightfully lead Islam], in the seventh century, and a long history of marginalization by the Sunni majority. Islam’s dominant sect, which roughly 85 percent of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims follow, viewed Shia Islam with suspicion, and extremist Sunnis have portrayed Shias as heretics and apostates.”

While the Shia-Sunni divide begins to explain some of the complications Washington has in working with Tehran, it is not the sole factor.

Richard N. Haass, former director of policy planning for the U.S. State Department, wrote in an article submitted to Project Syndicate that the Middle East’s problems run much deeper than sectarianism: “It is a region wracked by religious struggle between competing traditions of the faith. But the conflict is also between militants and moderates, fueled by neighboring rulers seeking to defend their interests and increase their influence. Conflicts take place within and between states; civil wars and proxy wars become impossible to distinguish. Governments often forfeit control to smaller groups—militias and the like—operating within and across borders. The loss of life is devastating, and millions are rendered homeless.”

In this quote, Mr. Haass was comparing the Middle East to 17th century Europe, but it still succinctly explains the complexities of the region today.

His feelings for the Mideast? “For now and for the foreseeable future—until a new local order emerges or exhaustion sets in—the Middle East will be less a problem to be solved than a condition to be managed.”

With the continuing wave of government upsets and civil wars, the United States can bank on continuing Shia-Sunni clashes.

Historical Alliances

Islam is just one side of Iran’s complex cultural identity. The other is much more ancient: that of Persia’s imperial past. The greatest example of this is Cyrus the Great, who lived from about 590 to 529 BC. The Iran Chamber Society described him as “upright, a great leader of men, generous and benevolent.”

Cyrus treated his subjects well and he even received a favorable report from the ancient Israelites in the Old Testament of the Bible: “Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia…he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom, and put it also in writing, saying, Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth has the Lord God of heaven given me; and He has charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Who is there among you of all His people? The Lord his God be with him, and let him go up” (II Chron. 36:22-23).

King Cyrus ushered in a golden age, but it was short-lived.

Vijay Shankar, a retired Indian navy vice admiral, wrote about Iran’s historical motivations in an essay on his website “Strategic Dialogues on Geopolitics, Security and Strategy”: “The golden period of Cyrus the Great was followed by a cycle of continuous turmoil when Persia was overrun frequently and had its territorial contours ravaged and reshaped through the centuries. Invaded and occupied by Greeks, Parthians, Sassanids, Ottomans, Arabs, Mongols and often drawn into and distressed by the affairs and struggles of great powers, Persia has tenuously held on to its past and its civilizational identity.”

While Persia “tenuously” held onto its identity, it did still hold on to it. Islam is the most obvious characteristic of Iran today, but its imperial identity has remained under the surface.

Recall Mr. Rouhani’s inaugural address: “People want to live better, to have dignity as well as a stable life. They also want to recapture their deserving position among nations.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRecapture their deserving position among nations. This is not speaking of Islam. Rather, it is clearly harkening to the model of preeminence started by Cyrus.

Mr. Shankar continued by explaining Iran’s dual national character. He stated that the Islamic conquest of AD 635-656 created an “abiding tension between the deep rooted Persian distinctiveness and the new Islamic identity; this stimulus is most apparent in its dealings with other nations and remains to this day.”

This two-sided identity is a core reason the United States has long found it difficult to read Iran’s intentions. The nation is pulled in two very different directions: to the west are the Arab states governed by the tenants of Islam. To the east are Asia and Russia.

Historically, Persia had strong ties to its neighbors China, Russia and Mongolia. For example, Russians (as the Medes) were part of the Medo-Persian (or Achaemenid) Empire. Also, China used to ship goods through Persia as part of the Silk Road. There is a rich history of economic, military and governmental collaboration.

These bonds are still in place today and are being rapidly strengthened.

For instance, President Rouhani stated: “Not only is Russia a neighbor with a long-standing history of relations with Iran, but also the expansion of cooperation and partnership between the two countries will certainly pave the ground for creation of a secure region” (Tasnim News Agency).

Some Russians hope to get more out of the nuclear negotiations with Iran than disarmament. The Fars News Agency quoted a prominent Russian businessman: “We hope the positive and constructive approach seen in the negotiations will leave positive effects on the economic ties between Iran and Russia.”

Iran is also becoming an increasingly important source of oil for China, and Tehran has called on Beijing to argue its case at the nuclear talks. In response, the Chinese ambassador to Iran stated that “I ensure that we will back Iran’s stance in the upcoming negotiations…” (The Diplomat).

Closer collaboration between Iran, Russia and China emphasizes America’s continued decline from its position as lone superpower. CBS News wrote: “China’s president called…for the creation of a new Asian structure for security cooperation based on a regional group that includes Russia and Iran and excludes the United States.”

Which Way?

As events heat up in the Middle East and globally, what the U.S. needs to know is what part of Iran’s personality will be dominant. Will it be the Shia Islamic side or its Persian cultural identity? Will it swing more to the Arab Middle East or the Asiatic East?

Unknown to most, the Bible details both Iran’s past (as seen earlier with the passage about Cyrus) and also its future through prophecy.

Bible prophecy—which can be likened to history written in advance—makes up a full one-third of its pages. Its purpose is twofold: to allow diligent readers of the Bible to know what events will befall the Earth, but also to prove the Book’s authority as the Word of God.

An example of the latter relates to Persia and can be found in the biblical book of Daniel. Real Truth Editor-in-Chief David C. Pack detailed this proof in his two-part article series The Mideast in Prophecy—Today’s Unrest! – Part 1.

He wrote: “Chapter 11 verse 2 begins covering persons and events that immediately lose the average Bible reader who would have no clue what they mean. But you can understand. History is our constant guide. Read verses 2 and 3: ‘Behold, there shall stand up yet three kings in Persia; and the fourth shall be far richer than they all: and by his strength through his riches he shall stir up all against the realm of Grecia. And a mighty king shall stand up, that shall rule with great dominion, and do according to his will.’

“Who are these four kings—where the fourth is greater than the first three? And who is the ‘mighty king’? Daniel was speaking of kings Cambyses, Smerdis and Darius of Persia as the first three, with Xerxes being historically the greatest and richest of the four. History shows it was Xerxes who did ‘stir up’ war with Greece.”

God’s Word is filled with such proofs of its validity. To learn more, read Mr. Pack’s booklet Bible Authority...Can It Be Proven?

But the other side of prophecy is to detail events that are still in the future. Much of what is written in the Bible’s pages applies to today—and the next few years. Notably, it describes three power blocs that will dominate the world stage. Two of these coalitions are known as the “king of the north” and “king of the south” (both described in Daniel 11). Psalm 83 also describes a moderate Muslim confederation that will align with the king of the north.

Persia is nowhere to be found in the descriptions for these power blocs. From all indications, this means Iran will be part of the “kings of the east,” which are mentioned in Revelation 16:12. This will be an alliance of Asian nations, with China and Russia working together.

How does all of this play into relations between Tehran and the U.S.? The two may work together for a short time and in small ways. But news headlines—and Bible prophecy—indicate Iran will turn to Russia and China as America’s global role diminishes.

More on Related Topics:

- The Last U.S.-Russian Nuclear Pact Is About to Expire, Ending a Half-Century of Arms Control

- Explainer: What Is President Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ and Who Has Joined So Far?

- China and Japan, Uneasy Neighbors in East Asia, Are at Odds Again

- Is Peace in Ukraine Any Closer After Trump-Zelenskyy Talks?

- Explainer: Why Is Fate of Donetsk Region a Sticking Point in Talks on Ending War in Ukraine?