Thinkstock

Thinkstock

Article

The trend of seemingly positive dealings between the two nations must be viewed through the lens of Iran’s history with the U.S.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowRelations between Iran and the United States have been rocky for decades. At one end of the spectrum, Iran has been linked to numerous terrorist activities against the West—while the U.S. has responded with everything from outright retaliation to economic sanctions. At the same time, opposite these aggressive actions have been diplomatic concessions.

Gabriel Duval/AFP/Getty Images

Gabriel Duval/AFP/Getty Images

Within the past year, relations appear to have taken a slightly friendlier tone, with the drumbeat of war from the last few decades fading to a faint background noise. Diplomatic courses are being pursued. Mindsets on both sides appear to be changing. Hopes for a peaceful outcome are high.

“For more than 100 years, the United States and Iran have engaged in an ambivalent relationship,” an article titled “Frenemies: Iran and America since 1900” published in Origins stated. (The word “frenemy” means one who pretends to be a friend but is really an enemy.)

“Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, America and Iran have butted heads over issues as diverse as oil, communism, radical Islam, and nuclear proliferation, often framing their mutual antagonism as a clash between civilization and barbarism. Yet with a new administration in Washington eager to improve U.S. relations in the Muslim world and with young men and women calling for democracy in the streets of Tehran, the old ‘frenemies’ may find that they have more in common than they think” (ibid.).

Is a new day dawning in Iran-U.S. relations? Will tensions in the region push them to become unlikely partners? To best answer this question, it is necessary to peer into the history of Iran’s on-again-off-again dealings with the West.

Historical Perspective

Even though U.S.-Iranian relations officially started in 1883, most people understand their tumultuous history from the perspective of Tehran’s 1979 hostage crisis. During this time, Iran openly defied America on the world stage, as recounted by The History Channel.

Staff/AFP/Getty Images

Staff/AFP/Getty Images

“On November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking more than 60 American hostages. The immediate cause of this action was President Jimmy Carter’s decision to allow Iran’s deposed Shah, a pro-Western autocrat who had been expelled from his country some months before, to come to the United States for cancer treatment. However, the hostage-taking was about more than the Shah’s medical care: it was a dramatic way for the student revolutionaries to declare a break with Iran’s past and an end to American interference in its affairs. It was also a way to raise the intra- and international profile of the revolution’s leader, the anti-American cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The students set their hostages free on January 21, 1981, 444 days after the crisis began and just hours after President Ronald Reagan delivered his inaugural address.”

While the hostage situation is often considered the start of the two countries’ frequent stalemates, the seeds of conflict actually started with another Western power—Britain. The European nation had stepped in to help Iran centuries earlier with military and economic aid. It also assisted the deposed shah’s father, Reza Shah Pahlavi, at the time of the first world war. The clash is explained by this necessarily longer passage from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

“Until the beginning of World War I, Russia effectively ruled Iran, but, with the outbreak of hostilities, Russian troops withdrew from the north of the country…Jubilation was short-lived, however, as the country quickly turned into a battlefield between British, German, Russian, and Turkish forces. The landed elite hoped to find in Germany a foil [opposing force] for the British and Russians, but change eventually was to come from the north.

“Following the Russian Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the new Soviet government unilaterally canceled the tsarist concessions in Iran, an action that created tremendous goodwill toward the new Soviet Union and, after the Central Powers were defeated, left Britain the sole Great Power in Iran. In 1919 the Majles [Iranian parliament], after much internal wrangling, refused a British offer of military and financial aid that effectively would have made Iran into a protectorate of Britain. The British were initially loath to withdraw from Iran but caved to international pressure and removed their advisers by 1921.”

Yet the British were persistent about their involvement in Iran, which provided the Western power much needed oil resources.

Gabriel Duval/AFP/Getty Images

Gabriel Duval/AFP/Getty Images

“In that same year British diplomats lent their support to an Iranian officer…Reza Khan, who…had been instrumental in putting down a rebellion led by Mirza Kuchak Khan, who had sought to form an independent Soviet-style republic in Iran’s northern province…Reza Khan staged a coup in 1921 and took control of all military forces in Iran,” Britannica continued. “Between 1921 and 1925 Reza Khan—first as war minister and later as prime minister under Ahmad Shah—built an army that was loyal solely to him. He also managed to forge political order in a country that for years had known nothing but turmoil. Initially Reza Khan wished to declare himself president in the style of Turkey’s secular nationalist president, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk [a Sunni Muslim]—a move fiercely opposed by the Shiite ulama [head religious body]—but instead he deposed the weak Ahmad Shah in 1925 and had himself crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi.”

The new shah infuriated many religious clerics because he intended to make Iran a secular state as opposed to one driven by religious principles.

“A wide range of legal affairs that had previously been the purview of Shiite religious courts were now either administered by secular courts or overseen by state bureaucracies, and, as a result, the status of women improved,” Britannica further stated. “The custom of women wearing veils was banned, the minimum age for marriage was raised, and strict religious divorce laws (which invariably favoured the husband) were made more equitable.”

“Reza Shah’s need to expand trade, his fear of Soviet control over Iran’s overland routes to Europe, and his apprehension at renewed Soviet and continued British presence in Iran drove him to expand trade with Nazi Germany in the 1930s. His refusal to abandon what he considered to be obligations to numerous Germans in Iran served as a pretext for an Anglo-Soviet invasion of his country in 1941. Intent on ensuring the safe passage of U.S. war materiel to the Soviet Union through Iran, the Allies forced Reza Shah to abdicate, placing his young son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi on the throne” (ibid.).

New Generation

The latest shah was loyal to Western powers, which angered many Iranians.

“Mohammad Reza Shah succeeded to the throne in a country occupied by foreign powers, crippled by wartime inflation, and politically fragmented,” Britannica continued. “Paradoxically, however, the war and occupation had brought a greater degree of economic activity, freedom of the press, and political openness than had been possible under Reza Shah. Many political parties were formed in this period, including the pro-British National Will and the pro-Soviet Tudeh (‘Masses’) parties. These, along with a fledgling trade union movement, challenged the power of the young shah, who did not wield the absolute authority of his father.”

“Following the war, a loose coalition of nationalists, clerics, and noncommunist left-wing parties, known as the National Front, coalesced under Mohammad Mosaddeq, a career politician and lawyer who wished to reduce the powers of the monarchy and the clergy in Iran. Most important, the National Front, angered by years of foreign exploitation, wanted to regain control of Iran’s natural resources, and, when Mosaddeq became prime minister in 1951, he immediately nationalized the country’s oil industry. Britain, the main benefactor of Iranian oil concessions, imposed an economic embargo on Iran and pressed the International Court of Justice to consider the matter. The court, however, decided not to intervene, thereby tacitly lending its support to Iran” (ibid.).

The moves between the two nations were strategic. By nationalizing the oil industry, Iranians hoped to end British domination and regain the wealth of its own resources. On the other hand, the West considered a stable, secular Iranian government backed by foreign powers in its best interest.

“British leaders Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden pushed for a joint U.S.-British coup to oust Mosaddeq, and the election of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the United States in November 1952 bolstered those inside the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) who wished to support such an action.

“Within Iran, Mosaddeq’s social democratic policies, as well as the growth of the communist Tudeh Party, weakened the always-tenuous support of his few allies among Iran’s religious class, whose ability to generate public support was important to Mosaddeq’s government. In August 1953, following a round of political skirmishing, Mosaddeq’s quarrels with the shah came to a head, and the Iranian monarch fled the country. Almost immediately, despite still-strong public support, the Mosaddeq government buckled during a coup funded by the CIA. Within a week of his departure, Mohammad Reza Shah returned to Iran and appointed a new prime minister.”

“There was no further talk of nationalization, as the shah firmly squelched subsequent political dissent within Iran. In 1957, with the aid of U.S. and Israeli intelligence services, the shah’s government formed a special branch to monitor domestic dissidents. The shah’s secret police—the Organization of National Security and Information…developed into an omnipresent force within Iranian society and became a symbol of the fear by which the Pahlavi regime was to dominate Iran.”

This laid the groundwork for what would eventually be a major turning point in the relationship between the two countries.

Power Struggle

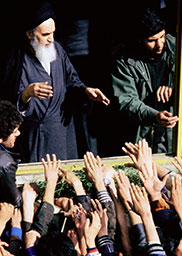

“By the 1970s, many Iranians were fed up with the Shah’s government,” The History Channel stated. “In protest, they turned to the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a radical cleric whose revolutionary Islamist movement seemed to promise a break from the past and a turn toward greater autonomy for the Iranian people. In July 1979, the revolutionaries forced the Shah to disband his government and flee to Egypt. The Ayatollah installed a militant Islamist government in its place.”

Ayatollah Khomeini wanted to orchestrate a revolution to bring Iranians back to their Islamic roots and restore Sharia—strict Islamic law—throughout the country. He routinely spoke out against the United States and Israel, which he referred to as the “Great Satan” and “Little Satan,” respectively.

After the revolution, he was given the title of “Supreme Spiritual Leader” for life—meaning that he became the highest-ranking Iranian cleric—a post that has only been given twice in Iran’s history. It is currently held by Ali Khamenei.

“Diplomatic maneuvers had no discernible effect on the Ayatollah’s anti-American stance; neither did economic sanctions such as the seizure of Iranian assets in the United States,” the outlet continued. “Meanwhile, while the hostages were never seriously injured, they were subjected to a rich variety of demeaning and terrifying treatment…The hostages never knew whether they were going to be tortured, murdered or set free.”

Because of the 1979 hostage crisis, the U.S. broke diplomatic relations with Iran in 1980—a policy still in practice today that fuels the power struggle between the two nations.

Surrounding Connections

After Iran’s Islamic Revolution, neighboring nations feared religious revolts could occur within their own borders. This was a significant factor for Iraq, which shares a border with Iran, to invade its neighbor in what was known as the First Persian Gulf War.

Joe Klamar/AFP/Getty Images

Joe Klamar/AFP/Getty Images

“When Iraq attacked Iran in September 1980, the United States did not immediately back either combatant,” the book Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979-1988 stated. “Yet by the summer of 1982, the Reagan administration had decided it could not tolerate an Iranian victory in the Iran-Iraq War. The fiery anti-American rhetoric out of Tehran continued, as did Iranian efforts to ‘export the revolution’ throughout the Islamic world. Concerned about Iranian threats to U.S. allies in the region, and about the flow of oil from the Persian Gulf to the West, the United States became ever more deeply involved in the conflict between Iran and Iraq.”

The book continued: “Beginning in mid-1982, Iran turned the tables on Baghdad and launched a counteroffensive into Iraq. The Reagan administration then began ‘tilting’ noticeably toward Iraq in its increasingly brutal and destructive war with Iran…It began to share with Baghdad some U.S. satellite intelligence regarding the location and apparent trajectory of Iranian troop formations…In these and other ways, it became clear that the Reagan administration had decided that the revolutionary government in Tehran must not be allowed to conquer Iraq, as Ayatollah Khomeini had vowed to do. The government in Tehran noticed the U.S. ‘tilt’ toward Iraq, which led to a further escalation of anti-American rhetoric and actions.”

In the end, Iraq was unsuccessful with the First Persian Gulf War. Yet the U.S.’s involvement produced more anti-American sentiments from Iran.

Recent Goodwill?

Since that time, Iran has seen various administrations that have both minimally supported and outright shunned any interaction with the West. Each change in leadership has resulted from the nation’s poor overall economic conditions: when the reforms of one regime do not work, another faction gains support and comes into power. This pattern of ongoing struggle between being under a more secular versus a religious-leaning government has been a mainstay of Iran’s history.

This additional factor also helps explain Iran’s continuing conflict with the U.S. and the difficulties the two countries have forming a partnership.

Currently, one of the largest areas of contention between the two countries is with nuclear weapons. Iran has been pursuing nuclear capabilities for the past decade, and is making significant strides—despite international demands to cease its efforts. According to the United Nations nuclear watchdog, Iran now has about 19,000 centrifuges, of which roughly 10,000 are operating. With nuclear power, the enriched uranium has either civilian or military uses—with the degree of refinement making the difference.

Iran has long maintained that it needs to enrich uranium to fuel a planned network of nuclear power plants and therefore not have to rely on foreign energy suppliers. The West, however, believes this to be a cover for a desire to have nuclear arms capability and threaten its long-time enemy, Israel. Iran openly supports Palestinian causes and has also been tied to supplying long-range missiles to the Palestinian terrorist organization, Hamas, for use on Israelis.

Yet while Israel and Iran stand on the brink, the U.S. appears to be taking a different path in its relationship with Iran. Since taking office in 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama has gradually chosen to pursue a less fiery course of action. Crippling sanctions were the mode of operation for a time, but with the election of a new Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, prospects of diplomacy and a palatable deal for the two nations seem possible.

In November 2013, the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Russia and China (known as the P5+1) struck a temporary deal in which Iran agreed to suspend some sensitive nuclear activities in exchange for limited relief from sanctions. The hope was to strike a permanent deal by July 20, 2014.

President Rouhani, a former chief nuclear negotiator for Tehran, stated in a Reuters article, “The major powers and Iran have agreed on two issues with Iran: We will continue our uranium enrichment activities and all sanctions on Iran will be lifted.”

He added that neither side would benefit if the talks were to collapse and any remaining disputes “can be resolved with goodwill and flexibility” (ibid.).

But as the deadline neared and countries involved with the deal continued wrangling the details of it, little seemed to change.

Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images

Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images

The Associated Press reported: “Tehran’s resistance was underscored…when Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei rejected pressure by the U.S. and its allies at the [latest round of talks in Vienna, Austria] to force Iran into making concessions. He said the Islamic republic would not give in to attempts by the West to greatly restrict its uranium enrichment program.

“Khamenei told top officials that the country should plan as if sanctions will remain in place so that Iran will be immune to outside threats.”

Others outside of Iranian circles are also skeptical about the apparent strengthening of the relationship and the concept of the U.S. and Iran moving past their differences.

“I don’t think we are anywhere near normalization of relations between the United States and Iran,” Suzanne Maloney, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution Saban Center for Middle East Policy, said. “This is in part because neither side has a compelling political interest in altering the context of their relationship. A nuclear agreement would be a very important arms control agreement, but it wouldn’t change the competing interests between the two countries and the conflict between the ideology of the Islamic Republic and that of Washington and the broader Western world.

“What we are seeing with respect to the nuclear agreement is extremely important and would be a major step forward. It would inevitably open up channels for additional dialogue on other issues, but it’s quite clear from the statements of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, and other senior leaders within Iran that the political climate there is not one in which they envision a warming of relations between the two countries—at least not at this time.”

Despite this, the rhetorical jostling between the two nations does appear to be slowing down.

With this understanding, further questions remain. What alliances does Iran have with other countries that could threaten Western interests? And what part will President Rouhani play in nuclear negotiations?

Part 2 of this article series will examine these questions and expand on Iran’s modern relationships with surrounding countries.

More on Related Topics:

- The Last U.S.-Russian Nuclear Pact Is About to Expire, Ending a Half-Century of Arms Control

- Explainer: What Is President Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ and Who Has Joined So Far?

- China and Japan, Uneasy Neighbors in East Asia, Are at Odds Again

- Is Peace in Ukraine Any Closer After Trump-Zelenskyy Talks?

- Explainer: Why Is Fate of Donetsk Region a Sticking Point in Talks on Ending War in Ukraine?