The Real Truth

The Real Truth

Article

Surrounded by clashing religious ideologies, unstable governments, and ongoing protests, the nation seems to stand steadfast in a tumultuous area.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowAt first glance, Jordan appears exactly as a first-time visitor might picture a Middle Eastern desert nation: dry, hot and desolate. Rolling hills of sandy soil stretch for miles, with barely a shrub able to thrive in its parched landscape. An occasional jutting palm tree, triad stone marker, or paved highway are often the only signs the rough terrain is populated.

In between vast expanses of desert, whitewashed stucco homes huddle at the foot of crimson mountains, which reach deep into a cloudless azure sky. Red, green, black and white Jordanian flags flap over government buildings and pictures of the nation’s leader dressed in military garb are posted on roadside billboards.

The Real Truth

The Real TruthYet a closer look into Jordan’s policies reveals a nation different from its neighbors. Situated in an area rocked by centuries-long conflicts, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a nation torn between its loyalty to surrounding nations and its desire to broker peace. It is one of only two countries other than Egypt that maintains relations with Israel and almost all of its Arab neighbors, Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, while enjoying close ties with the United States, Britain and other European nations.

Long considered a key piece of the Middle Eastern peace puzzle, Jordan’s bilateral ties uniquely position it as a regional mediator. This gives the country unusual insight into the kinds of problems that continually confront the area.

Visionary Leadership

Jordan is ruled by King Abdullah II, the son of the late beloved King Hussein, who reigned from 1953 to 1999. Because King Abdullah’s mother was a Briton who converted to Islam to marry his father, the young monarch spent his junior and high school years at a United States boarding school. After high school, he attended the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in Britain. In all, he spent 15 years away from Jordan.

The Real Truth

The Real TruthAfter returning home and serving in the Jordanian forces for several years, King Abdullah married Queen Rania in 1993, a Kuwaiti-Palestinian whose family fled to Jordan at the start of the Gulf War.

King Abdullah’s international experience, thirst for adventure, and tutelage from his well-known father gave him a unique perspective on world events. From an early age, he learned to speak impeccable English and how to fit in with Western culture while still embracing his own heritage.

Because of the king’s demonstrated leadership, Jordan is also one of the only countries other than Saudi Arabia that has not been significantly affected by the riots that have set the Middle East ablaze during the past year.

According to the CIA World Factbook, “Beginning in January 2011 in the wake of unrest in Tunisia and Egypt, several thousand Jordanians staged weekly demonstrations and marches in Amman and other cities throughout Jordan to protest government corruption, rising prices, rampant poverty, and high unemployment. In response, King Abdullah replaced his prime minister and formed a National Dialogue Commission with a reform mandate. Some opposition groups also called for sweeping political and constitutional reforms, particularly on a controversial election law.”

“The demonstrators in Jordan did not call for King Abdullah’s removal; they called for better governance, economic reform, and the removal of Prime Minister Samir Rifai, who is blamed for rising commodity prices and political stagnation,” an article by the Council of Foreign Relations stated. “Even demonstrating Islamists remain loyal to the monarchy. They want policy changes, not regime change.”

Ancient and Modern

In certain ways, Jordan has been an example for other Middle Eastern nations. For decades, the country has enjoyed relative peace under a stable monarchy and has gradually experienced an increased standard of living due to a tourism boom. The nation’s service industry accounts for over 60 percent of its GDP.

The Real Truth

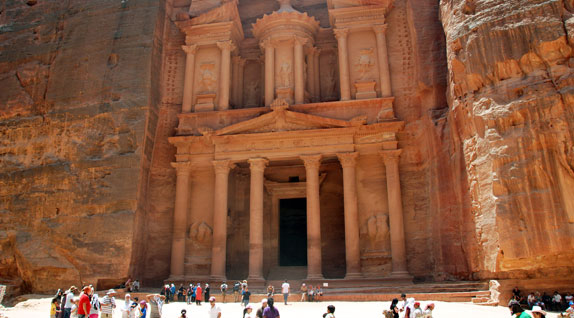

The Real TruthJordan boasts four UNESCO World Heritage sites, Petra (also one of the new seven wonders of the world), Quseir Amra, Um er-Rasas and the Wadi Rum Protected Area. One of the most visited is Petra, an ancient city hidden in the soaring 250-foot-high crags of a gorge.

Hundreds of years ago, the city was populated by more than 30,000 Nabateans, a pagan people who mastered the art of irrigation and gained great wealth from their city’s location along a trade route. Once the needs of traders changed, however, Petra lost its importance and vanished from history for 1,000 years.

According to local tradition and historical accounts, the Biblical patriarch Moses brought the children of Israel to the area surrounding Petra before entering into the Promised Land after fleeing Egypt. The valley is named Wadi Musa (“valley or river of Moses”) for this reason. A mosque on an adjacent mountain marks the spot where Moses’ brother Aaron is said to be buried.

On a recent trip to the Middle East, Editor-in-Chief David C. Pack and several news writers had the opportunity to visit the archeological remains of Petra and the surrounding Wadi Musa area to learn the history of its varied past and explore the region’s many caves.

A visit to Jordan reveals that it is a land where old meets new.

During the past 30 years, the mountainous area surrounding the old city of Petra has been transformed from a dusty wasteland, where Bedouin herders took shelter among the cracks of the rocks, into a thriving city. As opposed to decades earlier, complex self-sustaining irrigation systems dot the landscape, allowing for agricultural farming throughout the dusty area. The region also boasts six five-star hotels and numerous lavish restaurants. Most of the residents living around Petra proper are Bedouin villagers that were resettled into hillside homes and now make their living from local tourism.

Other areas around Jordan have also been developed into desert oases. Towering skyscrapers line the horizon of the country’s capital, Amman, and Aqaba, located on the Red Sea, is a coveted destination spot for scuba divers.

While Jordan’s people continue to advance, many parts of the nation are still surprisingly remote. Policemen patrol the desert on camels and many Bedouin still prefer to live in goat hair tents without modern necessities, using only what they can glean from their own flocks to survive.

In addition, water is still scarce in many parts of the country: “Available yearly per capita share of fresh water in Jordan is among the lowest in the world estimated at about 160 [cubic meters],” U.S. Agency for International Development reported. “This share is continuously decreasing and is forecasted to go down to 90 [cubic meters] by 2020.”

Many areas also remain impoverished.

“Poverty stands at 13.3% and there are 32 registered pockets of poverty in different areas of the country,” a United Nations Development Program report stated. “Furthermore, with the potential impact of the global economic crisis, there is a risk that the unemployment rate, estimated at 12.2%, may increase.”

Atypical Stance

Despite its population being 98 percent Arab, Jordan is one of the only Middle Eastern nations to oppose the Palestinian Authority’s September bid to gain United Nations acceptance as a state.

According to Israeli newspaper Arutz Sheva, “Jordan is continuing its efforts to convince the Palestinian Authority leadership to abandon its attempt to secure membership as a new country at the United Nations this September.”

The paper paraphrases al-Medinah, a Saudi Arabian newspaper as saying that “Jordan views the move as dangerous, and ‘advised’ PA Chairman and Fatah leader Mahmoud Abbas to abandon the attempt via Arab diplomatic channels...”

In addition, the paper stated that Jordan noted that “such a bid carries the additional risk of ruining the Palestinian Authority’s ability to fight for the ‘right of return’…”

The “right of return” is a claim by over five million foreign Arabs, descended from those who abandoned their homes as a result of Israeli warfare since 1948, that they should have the ability to return to their original lands in Judea, Samaria and Jerusalem.

According to The Jerusalem Post, “Many Palestinians…voiced hope that Jordan and Egypt, the only Arab countries that have peace treaties with Israel, would follow the Turkish example and cut off all relations with Israel.”

Yet Jordan is not only concerned with the effect such a move will have on the almost two million Palestinian refugees that reside within its borders, but also that the bid has the potential to destabilize the region.

“The PA’s unilateral move is perceived as highly premature and detrimental to the peace process by many in the international community and particularly by Washington, which has already declared it will oppose the move,” Ynet News reported.

Looking Ahead

In 2010, King Abdullah published a treatise on the future of the area titled Our Last Best Chance: The Pursuit of Peace, which discusses what he believes is the only way for the region to achieve peace: a two-state solution with compromises on both sides. He writes that if this cannot occur, then he believes peace is impossible.

In the preface of his book, he states, “Many in the West, when they look at our region, view it as a series of separate challenges: Iranian expansionism, radical terrorism, sectarian tensions in Iraq and Lebanon, and a long-festering conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. But the truth is that all of these are interconnected. The threat that links them is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

The king writes that during the 11 years of his reign, he has “seen five conflicts: the Al Aqsa intifada in 2000, the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 2006, and the Israeli attack on Gaza in 2008-9.”

“I believe we still have one last chance to achieve peace,” he states. “But the window is rapidly closing. If we do not seize the opportunity presented by the now almost unanimous international consensus on the solution, I am certain we will see another war in our region—most likely worse than those that have gone before and with more disastrous consequences.”

While King Abdullah has been known for his optimism regarding the peace process, he did admit to The Washington Post during an interview that his hopes are beginning to wane.

“…although we will continue to try to bring both sides to the table, I am—for the first time—the most pessimistic that I have ever been in 11 years. 2011 will be, I think, a very bad year for peace, and invariably when there’s a status quo, usually what shakes everybody up is some sort of military confrontation, at which point we all come running and screaming to pick up the pieces. Nobody wins in a war.”

Clearly, many unanswered questions plague the arid country—with the solutions to them as varied as those who create them. Given the delicate nature of the region’s situation, it is apparent much more will have to occur before Jordan can fully maximize its potential and create the peace it desires.

As one editorial writer in the Jewish-Herald Voice aptly stated regarding the future of the region, “The only thing that seems assured is that more uncertainty lies ahead…”

More on Related Topics:

- Anxious Travelers Scramble as Iran War Strands Tens of Thousands Across the Middle East

- War in the Mideast Widens as President Trump Says Strikes on Iran Could Last Several Weeks

- Iran Commemorates 1979 Revolution as Nation Is Squeezed by Anger Over Crackdown and Tensions with U.S.

- The Gaza Ceasefire Began Months Ago. Why Does Fighting Persist?

- Activists Say Iran’s Crackdown Has Killed at Least 6,221 People, as the Country’s Currency Plunges