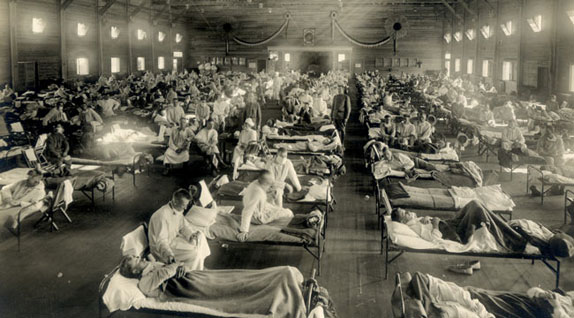

Courtesy Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/Contra Costa Times/KRT

Courtesy Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/Contra Costa Times/KRT

Article

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowA working-class father and his young family stand outside a clinic, masks over their faces. While his wife and children wait anxiously, worry creases his forehead. A mysterious virus has engulfed the country and he is concerned about its effects. What will happen to my family if I’m unable to work? he wonders.

Short-staffed hospitals overwhelmed with patients attempt to quarantine the infected before others contract the illness. But it is so contagious that even nurses fall prey.

Frustrated about the unexplained sickness, authorities shut down schools and force businesses to close, bringing the whole nation to a halt. Transportation systems all but stop, and health officials urge citizens not to leave their homes.

As the tired father waits in line, he recalls news reports about the illness ballooning into a pandemic-level outbreak. Glancing at his family, he wonders, Will we be next?

Although this description is eerily reminiscent of what is occurring today with the H1N1 virus, the year is 1918. And the influenza pandemic depicted above is not the current H1N1 swine flu outbreak, but the Spanish influenza that took the lives of 40 to 100 million people worldwide from 1918 to 1919.

Unparalleled in History

The early 20th-century pandemic started much the same as the current one. Three years before the 1918 virus took its worst toll, it first surfaced in birds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Recently published sequence and phylogenetic analyses suggest that the genes encoding the HA and neuraminidase (NA) surface proteins of the 1918 virus were derived from an avianlike influenza virus shortly before the start of the pandemic and that the precursor virus had not circulated widely in humans or swine in the few decades before…Regression analyses of human and swine influenza sequences obtained from 1930 to the present place the initial circulation of the 1918 precursor virus in humans at approximately 1915–1918.”

From 1915 to 1916, the United States suffered a hard-hit respiratory disease epidemic, upping the death toll resulting from pneumonia and influenza complications. Although mortality rates decreased by 1917, people’s weakened immune systems paved the way for the pandemic’s first wave in March 1918.

Spanish influenza initially appeared in Kansas in early spring, but was first recorded as extremely virulent in several soldiers in Boston, Mass., who had returned from fighting overseas in the First World War. The bustling port city became a breeding ground for the virus. Within three days, it infected 58 military personnel. The sick were sent to Chelsea Naval Hospital. From there, influenza infected civilians, with cases multiplying rapidly across the state and country.

The pandemic continued in three stages over a 12-month period: The first wave reached Europe, the U.S. and Asia in late spring and summer; a second—and more deadly—strain spread approximately six months later, wiping out entire families from September to November 1918; and a third wave struck in early spring of 1919.

“Most Viscous Type”

Unlike most viruses, which normally affect the very young, the weak and the elderly, the 1918 influenza targeted healthy adults from the ages of 20 to 40. Victims suffocated as their immune systems backfired—overreacted—filling their lungs with a reddish liquid, which often bubbled out of them as they died.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesA letter written by a military doctor on Sept. 29, 1918, described the dreadful conditions at Fort Devens, near Boston.

“These men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate.”

Later he wrote, “It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce, we used to go down to the morgue...and look at the boys laid out in long rows. It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle. An extra long barracks has been vacated for the use of the morgue, and it would make any man sit up and take notice to walk down the long lines of dead soldiers all dressed up and laid out in double rows” (PBS).

One pandemic survivor recounted the bodies that stacked up in Vancouver, Canada: “The undertaking parlours couldn’t handle the bodies as people died...they were having to use school auditoriums and places like that to store bodies temporarily” (The Canadian Press).

A survivor stated that in Washington, D.C., “the flu’s spread and the ensuing restrictions ‘made everybody afraid to go see anybody,’ he said. ‘It changed a lot of society…We became more individualistic’” (MSNBC).

Social Distancing

An effective measure at the time was social distancing—a method (related to the quarantine laws of the Bible) that public health officials in the 21st century still consider one of the most powerful ways to stop illness without a vaccine.

In St. Louis, Missouri, officials instantly closed schools, cancelled church services, and banned gatherings of more than 20 people, including funerals, weddings, dances and sports activities. As a result, the city’s death rate was only one-eighth that of Philadelphia—one of the cities hardest hit by influenza, which health authorities maintain took action too late.

St. Louis, however, did make one fatal mistake.

“On Nov. 14, 1918—in high spirits three days after the armistice that ended the war, and with influenza cases declining—the city reopened schools and businesses. Two weeks later, the second wave of the epidemic struck, this time with children making up 30 percent to 40 percent of the infections” (The New York Times).

Since the first wave of the pandemic did not hit as hard—merely infecting thousands, but not killing them—people did not take it seriously until it was too late. By the time influenza ran its full course, a fifth of the world population contracted the flu—killing as many as 100 million.

Throughout America, churches shut down, government banned public meetings, schools closed, businesses collapsed from lack of customers, state institutions became overrun with orphaned children, infected postal carriers were unable to deliver mail, and rancid garbage lined city streets. Decomposing bodies overflowed from morgues and had to be stored in nearby elementary schools. Wherever people ventured, the smell of rotting flesh haunted them.

In the book Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It, Gina Kolata, commentator for The New York Times, stated that if the Spanish Influenza were to strike the U.S. now, it would have devastating results. “If such a plague came today, killing a similar fraction of the U.S. population, 1.5 million Americans would die, which is more than the number felled in a single year by heart disease, cancers, strokes, chronic pulmonary disease, AIDS, and Alzheimer’s disease combined.”

This is not to mention that millions—perhaps even as many as 1.8 billion, according to current population estimates—would die worldwide.

One of the strangest parts of the virus, Ms. Kolata noted, is that scientists still have not been able to determine what made it so deadly.

“No one knows for sure where the 1918 flu came from or how it turned into such a killer strain,” she wrote. “All that is known is that it began as an ordinary flu but then it changed. It infected people in the spring of 1918, sickening its victims for about three days with chills and fever, but rarely killing them. Then it disappeared, returning in the fall with the power of a juggernaut.”

Snapshot of Today

As of this writing, the latest version of the swine flu has not attacked as vehemently as did later strains of the 1918 influenza. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates there are 182,166 suspected cases of H1N1 worldwide. However, unlike the Spanish flu, those who contract the H1N1 virus today are more likely to live than die—the WHO reports that only 1,799 people have fatally succumbed.

Nonetheless, the illness continues to spread. The most updated information from the WHO revealed newly detected, first-time cases in Ghana, Zambia and Tuvalu (the fourth smallest nation on Earth).

A map of the infected areas shows that even though almost all countries have reported only 10-50 virus-related deaths, cases have stricken all corners of the world. So far, the only places H1N1 has not claimed lives are Greenland, Mongolia and parts of Western Africa.

But the death toll continues to accelerate.

Last month, swine flu cases in Britain doubled to 100,000 in one week in July alone! The virus has had such a significant impact on the country that within minutes of opening, the National Pandemic Flu service website—capable of handling 1 million calls per week—crashed.

“Dr Alan Hay, director of the WHO’s London-based World Influenza Centre, said the extensive summer outbreak in Britain had not followed expected patterns and warned that the health department needed to be prepared for a more deadly form of the disease.

“‘We have been a little surprised by the degree of spread of this virus. A few weeks ago we anticipated that this was going to be a short series of outbreaks that would probably peter out before reappearing in the autumn or winter and that has proved not to be the case,’ he said” (Guardian).

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, recorded 569 new H1N1 infections in one day in August—the highest number ever reported in such a short time period. Around the same time, the Chinese Ministry of Health registered 132 new cases of H1N1 in two days, bringing the number of cases there to 2,861.

Even Martha’s Vineyard, a small island off the coast of Massachusetts known as a playground for the rich, was affected. A 26-year-old Brazilian man died after being diagnosed with H1N1. He is among 447 people in the U.S. since April 2009 whose deaths have been linked to the virus.

A startling report revealed, “Swine flu may infect half the U.S. population this year, hospitalize 1.8 million patients and lead to as many as 90,000 deaths, more than twice the number killed in a typical seasonal flu, White House advisers said” (Star-Telegram).

The U.S. military also reported another 67 confirmed cases of swine flu among soldiers in Iraq. Authorities suspect there could be dozens more.

Just the Beginning

Although the virus initially jumped from one country to another, sparking worldwide panic, deaths have been few and far between compared to other pandemics. But researchers who have studied the virus in the past, and the parallels of the 1918 strain to that of today, say it may only be in its initial stages.

“The Spanish and swine flu viruses are very similar although the current one does not seem to be as nasty—but it is in its early days yet,” John Powell, an associate clinical professor of public health at Warwick University in the United Kingdom, said in an interview with the British Daily Mail.

“There are enormous parallels with 1918 and our current pandemic,” he added. “They are spreading at a similar rate, but we don’t know if the virus will mutate…If it does, this is when it could become very dangerous. But we are working on vaccines and we hope that they will be sufficient” (ibid.).

The U.S. Health and Human Services originally ordered 120 million doses of the inoculation to use before the approaching flu season, but said that now only 45 million will be available by October due to production delays—leaving up to 200 million Americans not immunized.

Next month, Australia may be the first nation to begin vaccinating its citizens, making 2 million doses available. Already, “Australia’s death toll from the virus reached 128, and there are 460 people in Australian hospitals with H1N1, 94 of them in intensive care” (Bloomberg).

But the quantity available is still far less than that which was originally expected, and health officials agree that while vaccination is a start, it is not a surefire solution. The virus could morph and render all produced vaccines unusable, making social distancing (as with 1918) the best option.

In his book The Life of Reason, famed historian George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Judging from history, humanity is setting itself up to confront another “Mother of All Pandemics.” Will we learn from the past, and glean from the experiences that those, such as the father standing in line with his children in 1918, had? Or will we choose to ignore the clear pattern of history that always repeats itself?

To learn more about this topic, read our series on the Four Horsemen of the book of Revelation.

More on Related Topics:

- Afghan Hunger Crisis Deepens as Aid Funding Falls Short, UN Says

- Israel’s Longest War Is Leaving a Trail of Traumatized Soldiers, With Suicides Also on the Rise

- Maintaining Your Health as You Grow Older

- The Blind to See—Humanity’s Fight to Cure Blindness

- ‘Nightmare Bacteria’ Cases Are Increasing in the U.S.