The Real Truth

The Real Truth

Article

Renewed clashes between Jews and Muslims over Israel’s Temple Mount are set to dramatically affect international relations. The past provides clues as to how this will happen.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

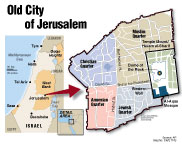

Subscribe NowAt the summit of a sloping pathway, one emerges into an almost park-like atmosphere. Trees, fountains and gardens dot the area and visitors mill about the dominating gold structure known as the Dome of the Rock. To the Muslim, this is Haram al-Sharif, or the Noble Sanctuary—Islam’s third holiest site. To the Jew, it is the Temple Mount—Judaism’s most sacred ground.

After 1,300 years of Muslim care, the area is distinctly Islamic: Light glints off the golden dome, complemented by mosaic-laden outer walls of summery greens, blues and yellows. At the top of the structure is an image of a full moon, which evokes the crescent moon symbol of Islam.

Despite the open spaces and well-maintained gardens, the location can hardly be described as peaceful. In fact, it is a battleground for Jews and Arabs. In September, beginning with Jewish Rosh Hashanah celebrations, Palestinian stone throwers met Israeli police in a show of aggression after Jewish radicals attempted to assert their right to pray there—something forbidden by Palestinian authorities and adhered to by most Israelis.

Since then, the conflict has spread throughout the region. An Israeli couple was shot dead in the West Bank in front of their four children, a Palestinian man stabbed two Israelis to death and was shot dead by police, four Israelis were wounded in Tel Aviv, and Palestinian clashes with Israeli police left over 14 Palestinians dead. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared that a “wave of terror” was occurring, which led many to fear a third Palestinian intifada (resistance or uprising) was taking form.

Clashes atop the mount are nothing new. It is easily the most coveted archeological, religious, historical and cultural plot of ground in the world. Even more, it is the epicenter of conflict in the Mid-East.

Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty Images

Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty ImagesChristianity and Judaism claim the site is Mount Moriah, where Abraham bound Isaac and the location of the First and Second Temples. Muslims say it is where the prophet Muhammad took his night journey to heaven on his horse to receive the mandate to pray five times per day. Christian heritage also connects to the mount, which carried the footprints of Jesus Christ and the apostles. In addition, it was a site of Catholic cathedrals during the Crusades.

BBC broadcast journalist Tim Franks put it this way: “If Jerusalem is the crucible of the Middle East Conflict, then the Old City is the crucible of the crucible, and the [Temple Mount] is the crucible of the crucible of the crucible.”

Mr. Franks took two tours of the Western Wall Tunnel at the base of the mount, each with a different guide. One was a Palestinian man, the other a Jewish woman. With the Palestinian guide, he was told, “There is no proof of a temple here. None at all.”

When pushed, the man conceded that “maybe” the Second Temple once stood on the site, “but I don’t have archaeological evidence.”

The Jewish tour guide claimed the contrary: “Wherever we dig, we find history.”

Nevertheless, Muslim authorities have banned archaeologists from examining the Temple Mount, and its physical history remains buried.

For over 2,900 years, religions, cultures and nations have vied for the ground. Great empires vehemently fought to keep it. Israel, Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome and Turkey have all triumphantly stood at the summit.

The one constant atop the Temple Mount has been violence and war. Through the centuries, there have been a few ceasefires and short periods of peace—usually fragile stalemates—but they have always given way to violence.

The rich history of the Temple Mount unlocks the source of the Mid-East conflict, identifies the major reoccurring players, and points to what is next for the site.

Modern Mount Violence

While Israel controls Jerusalem, a Muslim council, known as the Waqf, manages the mount—making the hill a flashpoint for violence. Haaretz summed up the conflict of interests between the two groups: “For a Muslim, the Al-Aqsa Mosque takes up the entire Mount, which Muslims call the Noble Sanctuary. The proof, say the Palestinians, is the Arabic name for the mosque. While the Israelis call the building Al-Aqsa, the Arabs call it Al-Qibli and note that it has no minaret. Al-Aqsa’s minarets are at the four corners of the complex and prove that the entire mount is a mosque—so all of it is holy.

“For this reason, many Palestinians believe it’s sacrilege whenever anyone from a different religion enters the Temple Mount. So if you mention the status quo as a claim against this viewpoint, all it does is add to the tension.”

Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty Images

Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty ImagesThe term “status quo” has done little to quell Palestinian fears that Israel plans to allow Jews to pray there. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has assured that he intends to keep the status quo and warned that Israelis are liable for their own actions if they visit the mount. However, hard-pressed Jews continue to assert their right to access—even own—the mount.

This is represented by a historical back-and-forth battle for control.

- In 1929, Arab-Israeli violence erupted, with Jews vying for control of the Western Wall (the only remaining part of the second Jewish Temple).

- During the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel conquered the mount, with a colonel declaring over his army radio, “The Temple Mount is in our hands!” (Jewish Virtual Library).

- In the 1980s, authorities uncovered a Jewish extremist plot to destroy the Dome of the Rock.

- After the 2000 Camp David peace talks, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak said the mount should be Palestinian controlled, but under the umbrella of Israeli sovereignty. In response, Palestinian officials publicly announced the Jewish Temple never stood on the mount and that there was no Jewish cultural link to the site.

These are oft-repeated sentiments. Al-Quds University stated on its website that “the Al-Aqsa compound cannot possibly be in the same place as the first or second temple,” adding that the First Temple was “a pre-monotheistic place where many gods were worshipped…dominated by Syro-Phoenician traits” to appeal “to pagan worshippers living in the area.”

Nathan Sharnansky, minister for Jerusalem and Diaspora Affairs, summarized the Palestinian argument to Haaretz as, “You [Israelis] have no right to exist in this country, you have no connection to it, get out of here.”

His response to such claims is: “One doesn’t have to be religious in order to understand that relinquishing the Temple Mount is not only relinquishing the past, it is primarily relinquishing the future. The future of all of us here.”

In short, Israelis claim this site as part of their historical heritage. But Palestinians say Jews have no place here. Thus, a shaky standoff forms—and continuous conflict.

Ancient Beginnings

The Temple Mount turf war reaches even further into the past. The land, which rises 2,428 feet above sea level between the Kidron and Tyropoeon valleys, has passed through the hands of great civilizations and empires.

Yet it all started with the biblical patriarch Abraham. The first recorded mention of Mount Moriah comes from the book of Genesis. After rescuing his nephew Lot from four Canaanite kings, Abraham met with King Melchizedek at the base of the mount.

Jewish scholar Doctor Benjamin Mazar placed the meeting between Abram and Melchizedek—known as “king of Salem”—in the En-Rogel valley (The Illustrated History of the Jews). Note that Salem was later renamed Jerusalem.

In his book Moriah, Andrew J. Gregg described the location of the valley: “From En-Rogel, the view of Mt. Moriah is grand, as it towers above the valley.”

After a meal, Melchizedek blessed Abraham (Gen. 14:19-20).

That night, the patriarch was blessed further: “The word of the Lord came to Abram…and He brought him forth abroad, and said, Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if you be able to number them: and He said unto him, So shall your seed be” (15:1-5).

The Hebrew word for abroad means “brought outside,” likely to the peak of Mount Moriah to look at the stars. Abraham then built an altar there and offered a sacrifice.

Later, the patriarch returned to the same spot after God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son. “And they came to the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the wood” (22:9).

God spared Isaac and blessed Abraham for his faithfulness.

Divided Family

Abraham’s ties to Moriah do not end there. He had two sons: first, Ishmael (by Hagar, a handmaid), then Isaac (by his wife, Sarah).

Though Abraham passed the birthright to Isaac instead of his firstborn, Ishmael was also blessed. His offspring became the Arab people. Ishmael’s 12 sons (Gen. 25:16) went on to form major Arab nations, not insignificant nomadic tribes as some believe. These peoples intermarried primarily with the Egyptians and were located southeast of Canaan, in the region of Arabia.

Isaac’s wife, Rebekah, had twins: Esau was the eldest and Jacob the younger. Esau lost the birthright—instead, it went to Jacob.

Esau married Mahalath, the daughter of Ishmael (28:9). The house of Esau, also known as the Edomites and Amalekites, gave rise millennia later to the Ottoman Turks, as well as the Seljuk Turks, who conquered and held most of Asia Minor, and the Caucasian Osmanli Turks, who controlled the Holy Land from AD 1070 until they surrendered it to the British in 1917.

Both Ishmael and Esau remained bitter for losing the birthright blessing. The jilted brothers jealously despised the descendants of Jacob (whom God renamed Israel).

Jaafar Ashtiyeh/AFP/Getty Images

Jaafar Ashtiyeh/AFP/Getty ImagesThis ancient family feud lingers today in the ongoing hostility primarily between the Muslim Palestinians (some of the descendants of Esau and Ishmael) and the modern Jewish state, allied with Anglo-Saxon nations (all the offspring of Jacob/Israel). The United States and United Kingdom, along with its commonwealth countries, received Abraham’s birthright. (Read America and Britain in Prophecy to learn more about the modern nations descended from ancient Israel.)

This backdrop frames the entire Mid-East conflict. And, like the skyline of the Old City of Jerusalem, the Temple Mount rises front and center in importance.

Israel Holds the Temple Mount

King David took Jerusalem about 1000 BC. The book of II Samuel reveals “the stronghold of Zion” is also “the city of David” (II Sam. 5:7). Zion is directly south of Mount Moriah.

Late in his life, David purchased the mount from Araunah the Jebusite for 600 shekels of gold. David constructed an altar there, which from that time was “the house of the Lord God” and “the altar of the burnt offering for Israel” (I Chron. 22:1). The aging king amassed the materials for the Temple, which his son Solomon completed. Notice: “Then Solomon began to build the house of the Lord at Jerusalem in mount Moriah, where the Lord appeared unto David his father, in the place that David had prepared in the threshingfloor of Ornan the Jebusite” (II Chron. 3:1).

The Temple was sided with immaculately cut white stone, which shone brightly in the sun. Twelve-foot walls surrounded the court and the porch at the entrance was about 200 feet high at its peak—about the height of a modern 20-story building. Two pillars stood at the front, each about 52 feet high and each made of at least 30 tons of brass (I Kgs. 7).

During the golden days of King Solomon’s reign, Israel enjoyed peace.

But things changed. Under evil kings of Judah, Mount Moriah hosted numerous pagan deities: Tammuz, Molech and Ashtaroth.

For example, King Manasseh erected a wooden image to the sex goddess Ashtaroth and placed it on Mount Moriah. He built altars for the stars in the two courts of the Temple. He even sacrificed his son to Molech (II Kgs. 21:6).

Simultaneously, hostile nations began attacking Israel. The Temple was looted by an Egyptian pharaoh (II Chron. 12:9). Later, Judah’s King Ahaz stripped Temple gold to buy Assyria’s protection (II Kgs. 16:8).

David’s descendants did not hold the mount for the long haul.

Exile and Return

Enter the Babylonians. Nebuchadnezzar II seized the Temple Mount and burned Solomon’s Temple to the ground, looting the gold and silver and sacred vessels (II Kings 24:10-13).

The Persians defeated Babylon and took the Jews as slaves (II Chron. 36:20).

Mahmud Hams/AFP/Getty Images

Mahmud Hams/AFP/Getty ImagesPersian King Cyrus sent the Jews back to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple (Ezra 1:1-3). Under the auspices of Zerubbabel, Ezra and Nehemiah, the Jews worked for 21 years to complete the Temple in 515 BC. This second structure was of lesser quality than the first.

After Alexander the Great died, his four generals grappled for control of Jerusalem. The Seleucid kingdom (started by one of Alexander’s generals) finally took Jerusalem around 200 BC.

Seleucid King Antiochus IV appointed his own high priest for the Temple, allowing him to more easily Hellenize the Jewish religion. Using this “puppet” priest, Antiochus forced the Jews to worship idols and eat pork (The Illustrated History of the Jews). He also forbade circumcision, which he viewed as mutilation, erected a statue of Zeus on the mount, and sacrificed pigs upon the altar. The Jewish Encyclopedia correctly identifies the transformation “of the sacred Temple at Jerusalem into a heathen one” as one of the fulfillments of the “abomination that makes desolate” mentioned in Daniel 11:31.

The actions of Antiochus led to the successful Maccabean revolution. The Romans then took over the land in 63 BC, and held the city for the next 500 years.

Herod the Great, whose father was an Edomite (Esau) and mother was an Arab (Ishmael), received kingship of Judea from Rome in 40 BC. After some resistance, he convinced the Jews to allow him to renovate the Temple and bring it to perfection (he also built it as a memorial to himself). Herod enlarged the mount to the size it is today. Some foundation stones were 40 feet long and over 600 tons, or 1.2 million pounds!

This was the same Temple, which took 46 years to complete, that Jesus visited throughout His life.

After yet another Jewish rebellion, Titus of Rome laid siege to Jerusalem, encircling it with armies. Once taken, Titus burned the Temple in AD 70 (exactly 656 years after the destruction of Solomon’s). The event echoes Christ’s warning in Luke 21:20 for the years just ahead: “And when you shall see Jerusalem compassed with armies, then know that the desolation thereof is near.” Armies surrounding Jerusalem is another clue to the abomination of desolation.

Roman soldiers looted the structure, dismantling every stone to pry out the melted gold. Titus then carried his spoils to Rome, including the Menorah and other sacred vessels.

Roman General Hadrian in AD 136 built a temple to Jupiter, which was likely placed to the south of the mount, desecrating the site with a pagan statue and placing a bronze image of himself in the courtyard.

Then between 330-640, the mount fell into disrepair and became a dump.

Muslim Conquest, Christian Crusades

By year 700, Muslims took Jerusalem and built a wooden Al-Aqsa Mosque on the foundation of Hadrian’s Temple to Jupiter. The Dome of the Rock was likely built on the remains of a Roman hexagonal entrance hall to the north.

Soon, Catholics controlled the mount. Christian Crusaders violently seized the Holy Land and, in the early 12th century, reconstructed an earthquake-damaged Al-Aqsa Mosque as the Temple Solomonis (headquarters of the fabled Knights Templar) and the Dome of the Rock, renamed the Temple Domini. Crusaders revamped both buildings and added altars, icons, new mosaics, and Christian inscriptions—crosses replaced all crescent moons (Crusader Archaeology).

Muslims recaptured their Haram al-Sharif in 1187 under the famed Saladin, reclaiming the two mosques on the mount. Islamic followers purged the Catholic icons and renovated the marble mosaics and inscriptions.

Islam saturated the region. The Islamic missionaries who most vigorously spread their religion through violence were those of the lineage of Esau, which included the Turks.

Fundacion Banco Santander/Public Domain

Fundacion Banco Santander/Public DomainEven in the Holy Land, Islam’s incremental influence was accompanied by population shifts as explained by the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica: “The spread of Islam introduced a very considerable Neo-Arabian infusion. Those from southern Arabia were known as the Yaman [a son of Esau] tribe, those from northern Arabia, the Kais (Qais). These two divisions absorbed the previous peasant population, and…nominally exist; down to the middle of the 19th century they were a fruitful source of quarrels and of bloodshed.”

Muslims controlled the mount and Jerusalem until 1917 when Britain took Jerusalem. This was the first time European visitors were allowed on the Temple Mount since 1187.

Even today, the ancient grudge match continues between the descendants of Abraham: The Palestinians and Israelis have daggers drawn in an uneasy stalemate atop the mount.

End of the War

Though Abraham’s descendants have had the spotlight, the likes of Babylon and Rome are also entangled in the drama on the Temple Mount.

The text of the Bible is much more than Hebrew literature or historical text—it also outlines how future events will unfold on today’s Noble Sanctuary.

For example, the actions of Antiochus IV and Titus were only types of a coming desolation of the Temple Mount. Again, Jesus said, “When you therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in the holy place, (whoso reads, let him understand)” (Matt. 24:15). This is preceded by “Jerusalem compassed with armies” (Luke 21:20).

Tied to these events—the final and ultimate fulfillment of “the abomination of desolation”—is a figure known as “the man of sin” sitting “in the temple of God” (II Thes. 2:3-4).

These and other prophecies strongly indicate that Israel will be forced to take control of the mount for a time. This is the only way both a “holy place” and “temple of God” can be present there. Such actions are sure to put tremendous strain on long-held alliances, including between the United States and Israel.

When will all these events occur? The prophet Daniel places their fulfillment at the “time of the end” (Dan. 11:40). This is the time we live in today. And the system of the long-forgotten players—Rome and Babylon—will return with a starring role.

The board is set. The pieces are in motion. Who will stand victorious on the Temple Mount?

More on Related Topics:

- Anxious Travelers Scramble as Iran War Strands Tens of Thousands Across the Middle East

- War in the Mideast Widens as President Trump Says Strikes on Iran Could Last Several Weeks

- Iran Commemorates 1979 Revolution as Nation Is Squeezed by Anger Over Crackdown and Tensions with U.S.

- The Gaza Ceasefire Began Months Ago. Why Does Fighting Persist?

- Activists Say Iran’s Crackdown Has Killed at Least 6,221 People, as the Country’s Currency Plunges