MCT

MCT

Article

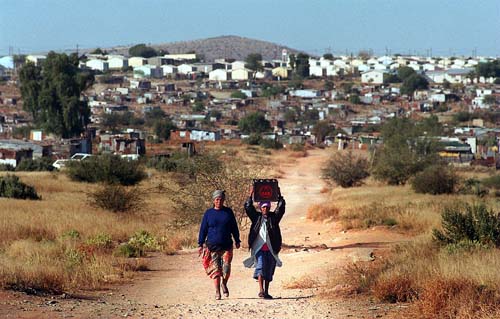

A recent trip to South Africa reveals a land of stark contrast and an ever-growing need for hope.

Learn the why behind the headlines.

Subscribe to the Real Truth for FREE news and analysis.

Subscribe NowJohannesburg, South Africa – Seeing a small child playing in the streets of a slum in South Africa is an unforgettable sight. The difference in lifestyle compared to that of a Westerner is so great that it is hard to fully comprehend.

Yet no matter the circumstances, a child is still a child. Many children in this world may not have the latest set of high-priced sneakers—in fact, some have no shoes at all!—but children still manage to have fun in whatever state they find themselves.

Wherever you go on this earth you can almost always witness the type of simple, exuberant joy that beams from the face of a child.

But try to imagine this South African setting imprinted in the memory of any visitor: Tiny eight-by-eight-foot shacks, cobbled together from rusty pieces of corrugated tin. Looking across these endless crammed groupings of shacks, a splash of muted colors reflect from the pieces of metal and other materials that have been scavenged and used to put together this meager existence. But the color that stands out the most is a lifeless brown—coming from the dusty, garbage-ridden dirt between the “homes” and the rusted metal roofs. Often, you will see items on top of the tin holding it down—old vehicle seats and other car parts, rusted out bed frames, and stones. Smoke fills the air, rising from distant piles of burning garbage. There is no running water and often no electricity. Using a car battery to power a television for a few hours each evening is considered a luxury.

This is what millions call home.

But South Africa is somewhat different from other African countries. A recent visit revealed to me and a fellow writer that South Africa is a land of stark contrast. Having been to East Africa (Nairobi, Kenya, and rural areas of western Kenya), it seemed as if South Africa was an intertwining of a typical African country with a modern Western one.

Several contrasts particularly stood out in our eyes. South Africa is a story of great wealth and immense poverty—robust economies and faltering infrastructure—state-of-the-art healthcare and a widespread epidemic of AIDS—Mercedes-driving yuppies and endless intersections lined with beggars—peaceful, gated communities and rampant crime.

The BBC described it this way: “It’s an old truism that South Africa is a land of two realities. It has never been more than a short drive from lush gardens and shopping malls to tin shanties and open sewers.”

We experienced this firsthand.

Statistics Speak for Themselves

One visit to any country cannot provide the full perspective, background and context needed to understand the conditions there. However, South Africa has been the subject of international news for years. In the early 1990s, and previously, the nation hit world news because of the system of apartheid and the drastic change from it that followed.

Then, as the years progressed, other news came from South Africa. Stories of violent crime—rape, robbery, murder and mayhem—were commonly reported.

Consider some of the latest facts:

On average, 50 people are killed each day. Johannesburg, the nation's largest city, is one of the most violent places on earth outside a war zone.

A staggering 150 women a day report being raped. One can only imagine the numbers who do not report this atrocity. To place this statistic in a more vivid perspective, BBC News reports that “one in four girls faces the prospect of being raped before the age of 16…” Or put another way, “It is a fact that a woman born in South Africa has a greater chance of being raped, than learning how to read.”

From 1992 to 2002 sexual violence against children has increased a staggering 400%. And baby rape is not uncommon and not a new phenomenon either!

As of the year 2000, 50% of the 43 million South African citizens lived below the poverty line.

Here are a sampling of newspaper headlines from just a few days in April 2007: “Woman dies in bus crash”; “Three die in lorry crash”; “Hijackers shoot man after bump”; “Taxi crashes into accident scene”; “Sergeant shot with his pistol”; “12 hurt in Joburg crash”; “Highway chaos at roadblocks”; “Three boys shot in error in brother feud”; “Teens killed in E Rand crash”; “Three killed as car rolls at De Deur”; “Woman killed for her intestines”; “One killed as two trucks collide”; “Man lying in road, shot in the head”; “More arrests over gang rape of pregnant woman.”

What kind of future does a child growing up in a South African slum have when she has a 25% chance of being sexually assaulted before reaching age 16? Innocence is being ripped away from children who deserve so much better.

Incessant Crime

Crime is reported daily, dominating the headlines. But because of the rampant crime, many incidents fail to be reported. Because of the poverty, many see stealing as the only option. One person broke the window of a car for a slice of pizza. A man was killed in Cape Town by an angry mob after stealing two bags of potatoes and a pumpkin.

MCT

MCTOn our first night in Johannesburg, we were confronted by a man at an intersection who wanted money. With luggage in the car, we clearly looked like tourists. After we declined, he continued to stare at us, his eyes cold and piercing. Later that night, it occurred to me that many in the depths of poverty must face the temptation to demand money instead of ask for it. A very fine line certainly crossed by thousands—at the expense of thousands.

What makes this problem worse is the senseless violence that accompanies it. People not only steal, they commit horrific crimes because they can—often killing the victim.

We learned that the streets and slums are filled with drugs, alcohol and guns. Reportedly, one can buy an AK-47 without any problem. You can also “rent a gun” with ammunition for one-time “needs.” Out of the 14 million guns that are estimated to be on the streets, only four million are legally registered (BBC).

MCT

MCTAs for rape, many don’t even consider it a crime. “In a related survey conducted among 1,500 schoolchildren in the Soweto township, a quarter of all the boys interviewed said that ‘jack rolling’—a South African term for recreational gang rape—was fun. More than half the interviewees insisted that when a girl says no to sex she really means yes” (ibid.).

In addition, sodomy is not viewed as rape; therefore, it incurs a smaller charge and sentence. To put it bluntly, men can never be the victims of rape, because of a ridiculous law.

To protect citizens from the rampant crime and to make people feel secure, South Africa has built what has been termed the “architecture of fear.” Houses are surrounded by walls, razor wire, high-voltage fences, burglary bars and security systems. Lives are shrouded in fear. And if they are ever tempted to forget it, the architecture of fear is a continuous reality check.

The Deputy President of South Africa recently asked, “When did South African society lose its morals?” (Cape Argus). She continued, “Why do some people get joy out of giving other people pain?…Has life become cheap?...Why is it that…the crime that we continue to grapple with is so violent?”

The reality is that human nature is violent. (To learn more, you may wish to read Did God Create Human Nature?)

Limping Infrastructure

MCT

MCTWhile driving the highways of Johannesburg you immediately notice a sense of general disregard for certain laws. You can see a man on the side of a busy highway trying to stay warm near a fairly large fire. You can see children in the back of pick-up trucks speeding along. In some instances, cars do not stop at stop signs; they simply slow down.

This led us to ask, “Where are the police? Why can’t more order be achieved?”

A recent story in The Citizen highlights the problem. Titled “SA drivers high on the highway,” the article reports that drugged drivers are becoming a greater problem than drunk drivers. “Although the South African Road Traffic Act prohibits people from driving while drunk or ‘under the influence of a drug having a narcotic effect,’ drugged drivers have little to fear…The police simply do not have the resources to routinely test motorists for narcotics use.”

MCT

MCTIn effect, we cannot even know how big this problem is because the police are unable to monitor it. A spokesman for the Automobile Association claims that 1 in 16 motorists are drunk after dark, and as many as 1 in 10 are high. Since a system is not in place to charge these individuals, if someone is caught, he is simply required to sit alongside the road until sober!

During our travel to Johannesburg, we also heard that an entire section of the city was without power. It happened to be an area we visited just a few days later. The Citizen reported that “chaos erupted as the outage and other isolated outages struck the East Rand.” This instance is just one example of the country’s overtaxed electric system.

While, in some regards, the nation is booming, other areas of infrastructure are faltering. Some say this is the legacy of the previous government. But South Africa simply went from one form of government that had its problems to another form of government that has its problems—period. The end result: millions still suffer.

RCG

RCGDoes this mean that the government is standing idly by as all this crime occurs? No. Certain crime is declining. The economy is improving. Public debt has been cut by 50% since 1999. Electricity is being directed into townships that never had power. Also, South Africa remains a large player on the world scene and the dominant force in Africa, often mediating conflicts between countries on the continent.

Searching for Hope

Despite the obvious problems, the individual South African, just like any other person on earth, desires and is seeking a life of happiness and fulfillment. Many in South Africa turn to alcohol and drugs.

When asked about the change in South Africa in the last couple of decades, a woman stated, “There has been no change physically in my life, but I am optimistic” (BBC). On the other hand, many claim that South Africa’s crime problem is insoluble. Others claim there are still inequalities between races. But how will equality be achieved?

A question must be asked: What can solve the social scourge of violent crime in South Africa? Where is the hope and happiness for that child playing in the dirt? A street youth said, “I was born in a cruel world, I’m living in a cruel world, and I’ll die in a cruel world” (ibid.).

The answer to that boy—and to every other child—is that there is hope. This magazine’s message is one of hope and happiness. It explains that there is a future ahead for South African children that few understand. Despite today’s terrible headlines, there is good news on the horizon for South Africa.

However, if nothing changes, chances are that innocent child in the slum may lose his or her innocence, growing up in a country of crime.

No man can solve all the problems of the South African. I close with a quote from The Real Truth magazine’s predecessor, The Plain Truth: “Even with the best of intentions, one can only help in a small way. But God has a plan that includes all the [South Africans]. And when it happens—and it will happen—all this will be just a memory.

“If only they could know this. If only they could believe it. It would make the waiting easier.”

More on Related Topics:

- In a Nigerian Village, Extremists Issued a Call to Prayer and Then Slaughtered Those Who Turned Up

- Sudanese Paramilitary Force Abducting Children in Darfur, Witnesses Say

- Nigeria’s Northeast Faces Worst Hunger in a Decade as Aid Cuts Hit Region, UN Says

- Uganda Shuts Down Internet Ahead of Election, Orders Rights Groups to Halt Work

- Sudan’s Top General Rejects U.S.-Led Ceasefire Proposal, Calling It ‘The Worst Yet’